Biographical sketch

Gordon Willard Allport, the youngest of four brothers, was born in Montezuma, Indiana, in 1897. Shortly after Gordon's birth, his father, a country doctor, moved the family to Ohio, and the younger Allport received his early education at Cleveland's rural free schools. He described the atmosphere in his family as permeated with feelings of trust and affection, as well as a special respect for work in the spirit of Protestantism.

<Гордон Олпорт (1897-1967).>

From an early age, Allport was a capable child; he characterized himself as a socially isolated individual, especially successful in literature and poorly prepared physically. At the insistence of his older brother Floyd, who was then a graduate student in psychology at Harvard University, he enters after graduation from the same university.

Although Allport took several courses in psychology at Harvard, he still majored in economics and philosophy. During his senior years, he participated in the development of a number of volunteer service projects. After graduating in 1919, Allport accepted an offer to teach sociology and English at Robert College in Constantinople, Turkey. Starting next year, he is receiving a fellowship for his graduate research paper in psychology, presented at the end of Harvard.

In 1922, Allport received his doctorate in psychology. His dissertation on personality traits was the first study of its kind to be done in the United States. Over the next two years Allport did research work at the Universities of Berlin and Hamburg in Germany and at Cambridge in England. After returning from Europe, he worked for two years as a lecturer at Harvard University in the Department of Social Ethics. Here he taught the course "Personality: its psychological and social aspects." It was the first course in personality psychology in the United States.

In 1926, Allport took up a post as assistant professor of psychology at Dartmouth College, where he remained until 1930. Then he received an invitation from Harvard to work in the same position at the Faculty of Social Relations. In 1942 he was awarded the title of professor of psychology, and until his death in 1967 he continued to hold this post. During his long illustrious career at Harvard, Allport influenced generations of students with his popular lecture course. He also received recognition as "the elder of American scientific research on personality problems."

Allport was a prolific author. His well-known publications include Personality: A Psychological Interpretation (1937); "Man and his Religion" (1950); "Becoming: the main provisions of the psychology of personality" (1955); "Personality and Social Conflicts" (1960); "Style and Personal Development" (1961) and "Jenny's Letters" (1965). He is also the co-author of two widely used personality tests, The A-S Response Study (with F. H. Allport, 1928) and The Value Study (with P. E. Vernon, 1931; revised by G. Lindsay in 1951 and again in 1960). A complete listing of his writings can be found in Man in Psychology (1968a). His autobiography is presented in Volume 5 of A History of Psychology in Autobiographies (Allport, 1967, pp. 3-25).

What is personality

In his first book, Personality: A Psychological Interpretation, Allport described and classified over 50 different definitions of personality. He concludes that an adequate synthesis of existing definitions can be expressed in the phrase: "Man is an objective reality" (Allport, 1937, p. 48). This definition is as comprehensive as it is inaccurate. Recognizing this, Allport went a little further in his statement that “personality is something and it does something. Personality is that which lies behind concrete actions within the individual himself” (Allport, 1937, p. 48). Avoiding the definition of personality as a purely hypothetical concept, Allport argued that it is a real entity related to the individual.

However, the question remains: what is the nature of this something Allport (1937) answered this question by proposing, as a result of repeated adjustments, a precise definition of personality: “Personality is the dynamic organization of those psychophysical systems within the individual that determine his characteristic behavior and thinking” (Allport, 1961, p. 28). What does all this mean? First, "dynamic organization" suggests that human behavior is constantly evolving and changing; according to Allport's theory, the personality is not a static entity, although there is some underlying structure that unifies and organizes the various elements of the personality. The reference to "psycho-physical systems" reminds us that both elements of "mind" and elements of "body" must be taken into account when considering and describing personality. The use of the term "defines" is a logical consequence of Allport's psychophysical orientation. In fact, the meaning of this expression is that the personality includes "determining tendencies" that, when appropriate stimuli appear, give impetus to actions in which the true nature of the individual is manifested. The word "characteristic" in Allport's definition only reflects the paramount importance he attaches to the uniqueness of any person. In his personological system, there are no two people alike. And finally, the words "behavior and thinking" refer to all types of human activity. Allport believed that personality expresses itself in one way or another in all observable manifestations of human behavior.

Giving this conceptual definition, Allport noted that the terms character and temperament often used as synonyms for personality. Allport explained how each of them can be easily distinguished from the individual. The word "character" is traditionally associated with a certain moral standard or value system, according to which the actions of an individual are evaluated. For example, when we hear that someone has a "good character", then in this case we are talking about the fact that his personal qualities are socially and / or ethically desirable. Thus, character is indeed an ethical concept. Or, to use Allport's formulation, character is estimated personality, and personality is not rated character (Allport, 1961). Therefore, character should not be viewed as a separate area within the personality.

Temperament, on the contrary, is the "primary material" (along with the intellect and the physical constitution) from which the personality is built. Allport considered the concept of "temperament" to be especially important when discussing the hereditary aspects of the emotional nature of the individual (such as the ease of emotional arousal, the prevailing background of mood, mood swings and intensity of emotions) (Allport, 1961). Representing one of the aspects of the genetic endowment of the individual, temperament limits the development of individuality. According to Allport's views, figuratively speaking, "you cannot sew a silk purse out of a pig's ear." Thus, as in any good definition of personality, Allport's concept clearly articulates what it is in essence, and what has nothing to do with it.

Personality trait concept

As pointed out at the beginning of this chapter, from the point of view of the dispositional approach, no two people are exactly the same. Any person behaves with a certain constancy and not like others. Allport explains this in his concept "features", which he considered the most valid "unit of analysis" for studying what people are and how they differ from each other in their behavior.

What is a personality trait? Allport defined a trait as "a neuropsychic structure capable of translating a variety of functionally equivalent stimuli and of stimulating and directing equivalent (largely stable) forms of adaptive and expressive behavior" (Allport, 1961, p. 347). Simply put, trait- it is a predisposition to behave in a similar way in a wide range of situations.For example, if someone is inherently timid, they will tend to remain calm and reserved in many different situations - sitting in class, eating in a cafe, doing homework in a hostel, shopping with friends. If, on the other hand, the person is generally friendly, he will be more talkative and outgoing in the same situations. Allport's theory states that human behavior is relatively stable over time and in a variety of situations.

Traits are psychological characteristics that transform many stimuli and cause many equivalent responses. This understanding of a trait means that a variety of stimuli can evoke the same responses, just as many responses (feelings, sensations, interpretations, actions) can have the same functional significance. To illustrate this point, Allport cites as an example the case of the fictional Mr. McCarley, whose main psychological feature is "fear of communism" (Allport, 1961). This trait of him makes equally "social incentives" for him, such as Russians, African-Americans and Jewish neighbors, liberals, most college teachers, peace organizations, the UN, etc. He labels all of them as "communists." Mr. McCarley may support a nuclear war with the Russians, write hostile letters to local newspapers about blacks, vote for extremist political candidates and right-wing politicians, join the Ku Klux Klan or the John Birch Society, criticize the UN, and/or take part in any of the a number of other similar hostilities. On fig. 6-1 schematically shows this range of possibilities.

Rice. 6-1. The universality of a trait is determined by the equivalence of the stimulus that activates the given trait and the responses it causes. (Source: adapted from Allport, 1961, p. 322)

Needless to say, a person can participate in such actions without necessarily having excessive hostility or fear of the communists. And besides, anyone who votes for right-wing candidates or is opposed to the UN does not necessarily fall into the same personality category. However, this example shows that personality traits are formed and manifested based on the awareness of similarity. That is, many situations perceived by a person as equivalent give impetus to the development of a certain trait, which then itself initiates and builds various types of behavior that are equivalent in their manifestations to this trait. This concept of the equivalence of stimulus and responses, united and mediated by a trait, is the main component of Allport's theory of personality.

According to Allport, personality traits are not associated with a small number of specific stimuli or responses; they are generalized and persistent. By providing similarity in responses to multiple stimuli, personality traits confer significant consistency in behavior. A personality trait is what determines the constant, stable, typical features of our behavior for a variety of equivalent situations. It is a vital part of our "personality structure." At the same time, personality traits can also be decisive in the pattern of human behavior. For example, dominance as a personality trait can manifest itself only when a person is in the presence of significant others: with their children, with a spouse or close acquaintances. In each case, he immediately becomes the leader. However, the dominance trait does not activate when this person discovers a ten dollar bill on the doorstep of a friend's house. Such a stimulus will rather cause the manifestation of honesty (or, conversely, dishonesty), but not dominance. Thus, Allport acknowledges that individual characteristics are reinforced in social situations, and adds: "Any theory that considers personality as something stable, fixed, unchanging, is wrong" (Allport, 1961, p. 175). In the same way, water can have the form and structure of a liquid, a solid (ice) or a substance like snow, hail, slush - its physical form is determined by the temperature of the environment.

It should be emphasized, however, that personality traits do not lie dormant in anticipation of external stimuli. In fact, people actively seek out social situations that contribute to the manifestation of their characteristics. A person with a pronounced predisposition to communicate is not only an excellent conversationalist when he is in a company, but also takes the initiative in finding contacts when he is alone. In other words, a person is not a passive “respondent” to a situation, as B. F. Skinner might believe, rather, on the contrary, the situations in which a person finds himself most often are, as a rule, the very situations in which he actively strives. get in. These two components are functionally interconnected. By emphasizing the interactions between human dispositions and situational variables, Allport's theory approaches the social learning theories of Albert Bandura and Julian Rotter (Chapter 8).

Traits » traits

It can be said that in Allport's system, personality traits themselves are characterized by "features", or defining characteristics. Shortly before his death, Allport published an article entitled "Revisiting Personality Traits" (Allport, 1966), in which he summarized all the data that could answer the question, "What is a personality trait?" In this article, he proposed eight main criteria for its determination.

1. A personality trait is not just a nominal designation. Personality traits are not fiction; they are a very real and vital part of the existence of any person. Each person has within himself these "generalized desires for action." In addition to "fear of communism", one can name such clearly recognizable personality traits as: "fear of capitalism", "aggressiveness", "meekness", "sincerity", "dishonesty", "introversion" and "extroversion". Allport's main emphasis here is on the fact that these personal characteristics are real: they really exist in people, and are not just a theoretical fabrication.

2. A personality trait is a more general quality than a habit. Personality traits determine the relatively unchanging and general features of our behavior. Habits, being enduring, refer to more specific tendencies, and therefore they are less generalized both in terms of the situations that "trigger" them into action, and in relation to the behavioral responses caused by them. For example, a child may brush his teeth twice a day and continue to do so because his parents encourage him to do so. It is a habit. However, over time, a child may also learn to brush their hair, wash and iron clothes, and tidy their room. All these habits, merged together, can form such a trait as neatness.

3. A personality trait is a driving or at least defining element of behavior. As already noted, traits are not dormant in anticipation of external stimuli that can awaken them. Rather, they encourage people to such behavior in which these personality traits will most fully manifest themselves. For example, a college student who is largely "sociable" doesn't just sit around waiting for parties to socialize. She actively seeks them out and thus expresses her sociability. So, personality traits "build" the action of the individual.

4. The existence of personality traits can be established empirically. Despite the fact that personality traits cannot be observed directly, Allport pointed out the possibility of confirming their existence. Evidence can be obtained by observing human behavior over time, by examining case histories or biographies, and by using statistical methods that determine the degree of overlap between individual responses to the same or similar stimuli.

5. A personality trait is only relatively independent of other traits. To paraphrase a well-known expression, we can say: "Not a single feature is an island." [This refers to the phrase of the English poet John Donne (1572-1631) "None of us is an island" (No man is an island). ( Note. ed.)] There is no sharp boundary separating one feature from another. Rather, personality is a set of overlapping traits that are only relatively independent of each other. To illustrate this, Allport cited as an example a study in which traits such as insight and sense of humor were highly correlated with each other (Allport, 1960). It is clear that these are different traits, but they are nevertheless somehow related. Since the results of correlation analysis do not make it possible to draw conclusions about causal relationships, we can assume that if a person has a highly developed insight, then it is very likely that he can notice the absurd aspects of human life, which leads to the development of his sense of humor. It is more likely, however, according to Allport, that the traits overlap initially, since the individual tends to respond to events and phenomena in a generalized way.

6. A personality trait is not synonymous with moral or social evaluation. Despite the fact that many traits (for example, sincerity, loyalty, greed) are subject to conventional social evaluation, they still represent the true characteristics of the individual. Ideally, the researcher should first detect the presence of certain traits in the subject, and then find neutral, rather than evaluative words to denote them. According to Allport, personologists should study personality, not character.

7. A trait can be viewed either in the context of the individual in whom it is found, or in terms of its prevalence in society. Let's take shyness as an illustration. Like any other personality trait, it can be considered both in terms of uniqueness and universality. In the first case, we will study the impact of shyness on the life of this particular person. In the second case, we will study this trait "universally", by constructing a reliable and valid "shyness scale" and determining individual differences in the parameter of shyness.

8. The fact that actions or even habits are not consistent with a personality trait is not proof that the trait does not exist. As an illustration, consider Nancy Smith, who exemplifies neatness and tidiness. Her impeccable appearance and impeccability in clothes undoubtedly point to such a trait as neatness. But this trait could in no way be suspected of her if we looked at her desk, apartment or car. In each case, we would see that her personal belongings were scattered, carelessly scattered, looking extremely sloppy and careless. What is the reason for this apparent contradiction? According to Allport, there are three possible explanations. First, not every person's traits have the same degree of integration. A feature that is the main one in one may be secondary, or completely absent in another. In Nancy's case, accuracy could only be limited to her own person. Secondly, the same individual may have contradictory traits. The fact that Nancy is consistent with her appearance and messy with her belongings suggests a limited amount of neatness in her life. Thirdly, there are cases where social conditions, much more than personality traits, are the primary "drivers" to certain behavior. If Nancy rushes to catch, for example, a plane, she may not pay attention at all to the fact that her hair is disheveled or her dress has lost its neat appearance along the way. Therefore, examples of the fact that not all of Nancy's actions correspond to her inherent propensity for accuracy are not proof that such a propensity does not exist in her at all.

Similar information.

Any person behaves with a certain constancy and not like others. Allport explains this in his concept of "traits", which he considered the most valid "unit of analysis" of personality. What is a personality trait? Allport defined a trait as "a neuropsychic structure capable of translating a variety of functionally equivalent stimuli and of stimulating and directing equivalent (largely stable) forms of adaptive and expressive behavior." Simply put, A trait is a predisposition to behave in a similar way in a wide range of situations. For example, if someone is inherently timid, they will tend to remain calm and reserved in many different situations, etc. Allport's theory states that human behavior is relatively stable over time and in a variety of situations.

Traits are psychological traits that transform multiple stimuli and produce multiple equivalent responses. According to Allport, personality traits are generalized and enduring. By providing similarity in responses to multiple stimuli, personality traits confer significant consistency in behavior. A personality trait is what determines the constant, stable, typical features of our behavior for a variety of equivalent situations. It is a vital part of our "personality structure". At the same time, personality traits can also be decisive in the pattern of human behavior. Allport acknowledges that individual characteristics are reinforced in social situations.

In his early work, Allport distinguished between commonalities and individualities. The former (also called measurable or legitimized) include any characteristics shared by a certain number of people within a given culture. The logic behind the existence of commonalities is that members of a given culture experience similar evolutionary and social influences and therefore develop, by definition, comparable patterns of adaptation. Personality traits (also called morphological) denote those characteristics of an individual that cannot be compared with other people. These are the "genuine neuropsychic elements that govern, direct, and motivate certain adaptive behaviors." This category of traits, which manifest themselves uniquely in each individual, most accurately reflects his personality structure. In the later years of his career, Allport called individual traits individual dispositions. The common features changed the name, becoming just personality traits.. The phrase "intrinsic to an individual" is now included in the definition of an individual disposition, but otherwise the definition remains the same as the earlier definition of a trait.

Allport proposed to distinguish three types of dispositions: cardinal, central and secondary.

The cardinal disposition so permeates a person that almost all his actions can be reduced to its influence. This highly generalized disposition cannot remain hidden. The presence of such a cardinal disposition or major passion can make its owner an outstanding figure in his own way. Allport argued that very few people have a cardinal disposition.

Not so comprehensive, but still quite striking characteristics of a person, called the central dispositions, are, so to speak, the building blocks of personality. Central dispositions are best compared to qualities given in letters of recommendation.. Central dispositions are tendencies in a person's behavior that others can easily detect.

Traits that are less visible, less generalized, less stable, and thus less useful for characterizing the personality are called secondary dispositions. This rubric should include food and clothing preferences, special attitudes, and situational characteristics of the person. Allport noted that one must know a person very intimately in order to discover his secondary dispositions.

Send your good work in the knowledge base is simple. Use the form below

Students, graduate students, young scientists who use the knowledge base in their studies and work will be very grateful to you.

Posted on http://www.allbest.ru/

Posted on http://www.allbest.ru/

Introduction

Chapter 1. The theory of personality and the concept of personality traits of G. Allport

1.1 Personality theory

1.2 The concept of personality traits

Chapter 2

2.1 Personal development

2.2 Mature personality

Conclusion

List of used literature

Introduction

Three decades ago, the best minds in psychology either steadily fell into the disease of a rigidly quantitative approach to the description of the phenomena studied, or honestly sought to trace unconscious motivation to its secret lair. Between these two rapids, Gordon Allport serenely pursued his own path, defending the importance of qualitative study of individual cases and emphasizing the role of conscious motivation. This refusal to swim in line with contemporary currents of thought sometimes manifests itself in the fact that Allport's formulations seem archaic and old-fashioned, but in other circumstances he appears as a champion of new and outrageously radical ideas.

His systematic position represents the distillation and development of ideas drawn in part from such authoritative sources as Gestalt psychology, the theory of William Stern, William James, and William McDougall. From Gestalt theory and from Stern came a distrust of the usual analytical methods of the natural sciences and a deep interest in the uniqueness of the individual, as well as in the congruence of his behavior. James' work is reflected not only in Allport's brilliant writing style, humanist orientation in dealing with human behavior and interest in the Self, but also in certain doubts about the possibility of adequately presenting and fully understanding the mystery of human behavior based on psychological methods. With McDougall's position, Allport brings attention to motivational variables, recognition of the important role of genetic and constitutional factors and the use of ideas about the "ego".

How can you characterize Allport's theoretical beliefs? Above all, his writings are an ongoing attempt to do justice to the complexity and uniqueness of individual behavior. Despite the blinding complexity of the individual, the basic tendencies in human nature exhibit a basic congruence or unity. Further, the conscious determinants of behavior are of overwhelming importance - at least for a healthy individual. The recognition of the congruence of behavior and the importance of conscious motivation naturally led Allport to the phenomenon often referred to by the terms "I" and "ego". Attention to the factors of the mind corresponds to Allport's conviction that a person is more a product of the present, not the past.

The object of work is a mature and healthy person.

The subject of the work is the theory of G. Allport.

The purpose of the work is to study the representation of a mature and healthy personality in the theory of G. Allport.

1) to study the theory of personality and the concept of personality traits of G. Allport;

2) consider the development of personality to a mature personality.

Chapter 1. The theory of personality and the concept of personality traits of G. Allport

1.1 Theorypersonalities

According to Allport, there is a gap between the norm and the pathology, the child and the adult, the animal and the human. Theories like psychoanalysis can be highly effective in representing disturbed or pathological behavior but are of little use when considering normal behavior. Similarly, theories that provide absolutely adequate conceptualizations of infancy or early childhood are inadequate as representations of adult behavior.

Allport states that his work is always oriented toward empirical problems rather than toward theoretical or methodological unity. He advocates the legitimacy of an open theory of personality, not a closed or partially closed one. Allport considers himself a pluralist working in line with systemic eclecticism. "A pluralist in psychology is a thinker who does not exclude any attribute of human nature that seems important." Personality for him is a riddle that needs to be solved as adequately as possible with the help of the tools of the middle of the twentieth century; so he posed other problems: rumors, radio, prejudice, the psychology of religion, the nature of attitudes, etc. To all these areas he applies concepts - eclectically and pluralistically, striving for what can give the most adequate consideration at the present level of knowledge. Thus, questions of the formal adequacy of his theory are of little importance to him.

In his first book, Personality: A Psychological Interpretation, Allport described and classified over 50 different definitions of personality. He concludes that an adequate synthesis of existing definitions can be expressed in the phrase: "Man is an objective reality." This definition is as comprehensive as it is inaccurate. Recognizing this, Allport went a little further in his statement that “personality is something and it does something. Martsinkovskaya T.D. History of psychology. M., 2014. P. 478.

Personality is what lies behind concrete actions within the individual himself. Avoiding the definition of personality as a purely hypothetical concept, Allport argued that it is a real entity related to the individual. However, the question remains: what is the nature of this something? Allport answered this question by proposing, as a result of repeated adjustments, an accurate definition of personality: "Personality is a dynamic organization of those psychophysical systems within an individual that determine his characteristic behavior and thinking." What does all this mean? First, "dynamic organization" suggests that human behavior is constantly evolving and changing; according to Allport's theory, the personality is not a static entity, although there is some underlying structure that unifies and organizes the various elements of the personality.

The reference to "psycho-physical systems" reminds us that both elements of "mind" and elements of "body" must be taken into account when considering and describing personality. The use of the term "defines" is a logical consequence of Allport's psychophysical orientation. In fact, the meaning of this expression is that the personality includes "determining tendencies" that, when appropriate stimuli appear, give impetus to actions in which the true nature of the individual is manifested. The word "characteristic" in Allport's definition only reflects the paramount importance he attaches to the uniqueness of any person. In his personological system, there are no two people alike. And finally, the words "behavior and thinking" refer to all types of human activity. Allport believed that personality expresses itself in one way or another in all observable manifestations of human behavior. Martsinkovskaya T.D. History of psychology. M., 2014. P. 482.

In providing this conceptual definition, Allport noted that the terms character and temperament were often used interchangeably with personality. Allport explained how each of them can be easily distinguished from the individual. The word "character" is traditionally associated with a certain moral standard or value system, according to which the actions of an individual are evaluated. For example, when we hear that someone has a "good character", then in this case we are talking about the fact that his personal qualities are socially and / or ethically desirable. Thus, character is indeed an ethical concept. Or, according to Allport's formulation, character is a person in evaluation, and personality is a character outside of evaluation. Therefore, character should not be viewed as a separate area within the personality.

Temperament, on the contrary, is the "primary material" (along with the intellect and the physical constitution) from which the personality is built. Allport considered the concept of "temperament" to be especially important when discussing the hereditary aspects of the emotional nature of the individual (such as the ease of emotional arousal, the prevailing background of mood, mood swings and intensity of emotions). Representing one of the aspects of the genetic endowment of the individual, temperament limits the development of individuality. According to Allport's views, figuratively speaking, "you can't make a silk purse out of a pig's ear." Thus, as in any good definition of personality, Allport's concept clearly articulates what it is in essence, and what has nothing to do with it. Stepanov S.S. Age of psychology: names and fates. M., 2012. P.356.

1. 2 The concept of personality traits

No two people are exactly the same. Any person behaves with a certain constancy and not like others. Allport explains this in his concept of "trait", which he considered the most valid "unit of analysis" for studying what people are and how they differ from each other in their behavior.

Allport defined a trait as "a neuropsychic structure capable of translating a variety of functionally equivalent stimuli and of stimulating and directing equivalent (largely stable) forms of adaptive and expressive behavior." Simply put, a trait is a predisposition to behave in a similar way in a wide range of situations. For example, if someone is inherently timid, they will tend to remain calm and reserved in many different situations - sitting in class, eating at a cafe, doing homework in the dorm, shopping with friends. If, on the other hand, the person is generally friendly, he will be more talkative and outgoing in the same situations. Allport's theory states that human behavior is relatively stable over time and in a variety of situations. Maklakov A.G. General psychology. SPB., 2015. P.324.

Traits are psychological characteristics that transform many stimuli and cause many equivalent responses. This understanding of a trait means that a variety of stimuli can evoke the same responses, just as many responses (feelings, sensations, interpretations, actions) can have the same functional significance.

According to Allport, personality traits are not associated with a small number of specific stimuli or responses; they are generalized and persistent. By providing similarity in responses to multiple stimuli, personality traits confer significant consistency in behavior. A personality trait is what determines the constant, stable, typical features of our behavior for a variety of equivalent situations. It is a vital part of our "personality structure." At the same time, personality traits can also be decisive in human behavior. For example, dominance as a personality trait can manifest itself only when a person is in the presence of significant others: with their children, with a spouse or close acquaintances. In each case, he immediately becomes the leader. However, the dominance trait does not activate when this person discovers a ten dollar bill on the doorstep of a friend's house. Such a stimulus will rather cause the manifestation of honesty (or, conversely, dishonesty), but not dominance.

Thus, Allport acknowledges that individual characteristics are reinforced in social situations, and adds: "Any theory that considers personality as something stable, fixed, unchanging, is wrong." In the same way, water can have the form and structure of a liquid, a solid (ice) or a substance like snow, hail, slush - its physical form is determined by the temperature of the environment.

It should be emphasized, however, that personality traits do not lie dormant in anticipation of external stimuli. In fact, people actively seek out social situations that contribute to the manifestation of their characteristics. A person with a pronounced predisposition to communicate is not only an excellent conversationalist when he is in a company, but also takes the initiative in finding contacts when he is alone. In other words, a person is not a passive “respondent” to a situation, as B. F. Skinner might believe, rather, on the contrary, the situations in which a person finds himself most often are, as a rule, the very situations in which he actively strives. get in. These two components are functionally interconnected.

It can be said that in Allport's system, personality traits themselves are characterized by "features", or defining characteristics. A personality trait is not just a nominal designation. Personality traits are not fiction; they are a very real and vital part of the existence of any person. Each person has within himself these "generalized desires for action." Allport's main emphasis here is on the fact that these personal characteristics are real: they really exist in people, and are not just a theoretical fabrication. Reinvald N.I. Psychology of Personality. M., 2015. P.312.

A personality trait is a more general quality than a habit. Personality traits determine the relatively unchanging and general features of our behavior. Habits, being enduring, refer to more specific tendencies, and therefore they are less generalized both in terms of the situations that "trigger" them into action, and in relation to the behavioral responses caused by them. For example, a child may brush his teeth twice a day and continue to do so because his parents encourage him to do so. It is a habit. However, over time, a child may also learn to brush their hair, wash and iron clothes, and tidy their room. All these habits, merged together, can form such a trait as neatness.

A personality trait is a driving or at least defining element of behavior. As already noted, traits are not dormant in anticipation of external stimuli that can awaken them. Rather, they encourage people to such behavior in which these personality traits will most fully manifest themselves. For example, a college student who is largely "sociable" doesn't just sit around waiting for parties to socialize. She actively seeks them out and thus expresses her sociability. So, personality traits "build" the action of the individual.

The existence of personality traits can be established empirically. Despite the fact that personality traits cannot be observed directly, Allport pointed out the possibility of confirming their existence. Evidence can be obtained by observing human behavior over time, by examining case histories or biographies, and by using statistical methods that determine the degree of overlap between individual responses to the same or similar stimuli.

A personality trait is only relatively independent of other traits. To paraphrase a well-known expression, we can say: "Not a single feature is an island." There is no sharp boundary separating one feature from another. Rather, personality is a set of overlapping traits that are only relatively independent of each other. Reinvald N.I. Psychology of Personality. M., 2015. P.316.

A personality trait is not synonymous with moral or social evaluation. Despite the fact that many traits (for example, sincerity, loyalty, greed) are subject to conventional social evaluation, they still represent the true characteristics of the individual. Ideally, the researcher should first detect the presence of certain traits in the subject, and then find neutral, rather than evaluative words to denote them.

A trait can be viewed either in the context of the individual in whom it is found, or in terms of its prevalence in society. The fact that actions or even habits are not consistent with a personality trait is not proof that the trait does not exist. Not every person's traits have the same degree of integration. A feature that is the main one in one may be secondary, or completely absent in another. The same individual may have contradictory traits. There are cases when social conditions, much more than personality traits, are the primary "drivers" to certain behavior. Abulkhanova-Slavskaya K.A. Life strategy M., 2011. P.125.

In his early work, Allport distinguished between commonalities and individualities. The former (also called measurable or legitimized) include any characteristics shared by a certain number of people within a given culture. We can say, for example, that some people are more persistent and stubborn than others, or that some people are more polite than others. The logic behind the existence of commonalities is that members of a given culture experience similar evolutionary and social influences and therefore develop, by definition, comparable patterns of adaptation. Examples include language skills, political and/or social attitudes, value orientations, anxiety and conformity. Most people in our culture are comparable to each other in these general ways.

According to Allport, as a result of such a comparison of individuals according to the degree of expression of any common feature, a normal distribution curve is obtained. That is, when the indicators of the severity of personality traits are depicted graphically, we get a bell-shaped curve, in the center of which is the number of subjects with average, typical indicators, and at the edges - a decreasing number of subjects whose indicators are closer to extremely pronounced. The figure (see Appendix 1) shows the distribution of indicators of the severity of such a common personality trait as “dominance-subordination”. Thus, the measurability of common features allows the personologist to compare one person with another in terms of significant psychological parameters (as is done in terms of general physical characteristics such as height and weight). Petrovsky A.V., Yaroshevsky M.G. History and theory of psychology. Rostov n./D., 2013. P.504.

Considering such a comparison procedure reasonable and useful, Allport also believed that personality traits are never expressed in exactly the same way in any two people.

In the later years of his career, Allport came to realize that using the term "personality trait" to describe both general and individual characteristics was problematic. Therefore, he revised his terminology and called individual traits individual dispositions. Common traits changed their name, becoming just personality traits. The phrase "intrinsic to an individual" is now included in the definition of an individual disposition, but otherwise the definition remains the same as the earlier definition of a trait.

Allport was deeply involved in the study of individual dispositions. Over time, it became obvious to him that not all individual dispositions are equally inherent in a person and not all of them are dominant. Therefore, Allport proposed to distinguish three types of dispositions: cardinal, central and secondary.

cardinal dispositions. The cardinal disposition so permeates a person that almost all his actions can be reduced to its influence. This highly generalized disposition cannot remain hidden, unless, of course, it is such a trait as secretiveness - the owner of it can become a hermit, and then no one will recognize his inclinations. central dispositions. Not so comprehensive, but still quite striking characteristics of a person, called the central dispositions, are, so to speak, the building blocks of personality. secondary dispositions. Traits that are less visible, less generalized, less stable, and thus less useful for characterizing the personality are called secondary dispositions. Petrovsky A.V., Yaroshevsky M.G. History and theory of psychology. Rostov n./D., 2013. P.507.

Chapter 2tie personality to a mature personality

2.1 Personal development

Not a single personologist, and especially Allport, does not believe that personality is just a set of unrelated dispositions. The concept of personality includes the unity, structure and integration of all aspects of individuality, giving it originality. It is reasonable, therefore, to assume that there is some principle that organizes attitudes, evaluations, motives, sensations, and inclinations into a single whole. According to Allport, in order to solve the problem of cognition and describe the nature of a person, constructs of such a level of generalization as I or lifestyle are needed. But all these terms contain too many ambiguous secondary shades of meaning and semantic ambiguities, so Allport introduces a new term - proprium.

According to Allport, proprium is a positive, creative, growth-seeking and evolving property of human nature. This is the quality "realized as the most important and central." We are talking about such a part of subjective experience as "mine". In general, this is all that we call "me". Fernham A., Haven P. Personality and social behavior. SPb., 2013. P.224.

Allport believed that proprium encompasses all aspects of the personality that contribute to the formation of a sense of inner unity. He considered proprium in the sense of the constancy of a person regarding his dispositions, intentions and long-term goals. At the same time, he did not consider the proprium to be a homunculus or "a little man living inside a personality." Proprium is inseparable from a person as a whole. This is a kind of organizing and unifying force, the purpose of which is the formation of the uniqueness of human life.

Allport identified seven different aspects of the self involved in the development of the proprium from childhood to adulthood.

Feeling your body. The first aspect necessary for the development of proprium is the feeling of one's body. During the first year of life, babies become aware of many of the sensations that come from muscles, tendons, ligaments, internal organs, and so on. These repetitive sensations form the body self. As a result, infants begin to distinguish themselves from other objects. Allport believed that the bodily self remains a lifelong support for self-awareness. However, most adults are not aware of the body's "self" until pain or an attack of illness occurs (for example, we usually do not feel our little finger until we pinch it in the door). Fernham A., Haven P. Personality and social behavior. SPb., 2013. P.226.

Feeling of self-identity. The second aspect of the deployment of proprium - self-identity - is most obvious when, through language, the child realizes himself as a definite and constantly important person. Undoubtedly, the most important starting point for a sense of wholeness and continuity of "self" becomes, over time, the child's own name. Having learned his name, the child begins to comprehend that he remains the same person, despite all the changes in his growth and in his interactions with the outside world. Clothes, toys, and other favorite things that belong to the child reinforce the sense of identity. But the feeling of self-identity does not arise overnight. For example, a two-year-old child may not be aware that he is cold, that he is tired, or that he needs to go to the toilet.

Feeling of self-respect. During the third year of life, the next form of proprium begins to appear - self-esteem. According to Allport, self-esteem is the feeling of pride that a child experiences when he does something on his own. Later, at the age of four or five years, self-esteem takes on a competitive tinge, which is expressed in the delighted exclamation of the child “I beat you!” When the child wins a game. Equally, the recognition of peers becomes an important source of self-esteem throughout the entire period of childhood. Allport G. Formation of personality. Selected works. / Per. from English. - M., 2012. P.293.

Expanding yourself. Starting from about 4-6 years of age, a person's proprium develops by expanding the boundaries of "self". According to Allport, children acquire this experience as they begin to realize that they own not only their own physical body, but also certain significant elements of the world around them, including people. During this period, children learn to comprehend the meaning of "mine". Along with this, manifestations of zealous possessiveness are observed, for example, “this is my ball”, “my own dollhouse”. My mother, my sister, my house, my dog are considered as components of “me”, and they must not be lost and protected, especially from the encroachments of another child.

An image of yourself. The fifth form of proprium begins to develop somewhere around the age of five or six years. This is the time when the child begins to learn what parents, relatives, teachers and other people expect from him, how they want him to be. It is during this period that the child begins to understand the difference between "I am good" and "I am bad." And yet, the child still has neither a sufficiently developed consciousness, nor an idea of what he will be like when he becomes an adult. As Allport said: “In childhood, the ability to think about yourself, what you are, what you want to be and what you should become, is only in its infancy.” Allport G. Formation of personality. Selected works. / Per. from English. - M., 2012. P.296.

Rational self-management. Between the ages of six and 12, the child begins to understand that he is able to find rational solutions to life's problems and to deal effectively with the demands of reality. Reflective and formal thinking appears, and the child begins to think about the process of thinking itself. But he does not yet trust himself enough to be morally independent; rather, he dogmatically believes that his family, religion, and peer group are always right. This stage of proprium development reflects strong conformity, moral and social obedience.

Personal desire. Allport argued that the central problem for a teenager is the choice of career or other life goals. The teenager knows that the future must be planned, and in this sense he acquires a sense of himself that was completely absent in childhood. Setting long-term goals, perseverance in finding ways to solve the tasks set, the feeling that life has meaning - this is the essence of personal aspiration. However, in youth and early maturity this desire is not fully developed, because a new stage of the search for self-identity, a new self-consciousness, is unfolding.

In addition to the above first seven aspects of proprium, Allport proposed one more - self-knowledge. He argued that this aspect stands above all others and synthesizes them. In his opinion, self-knowledge is the subjective side of the Self, which is aware of the objective Self. At the final stage of its development, proprium corresponds to the unique ability of a person to self-knowledge and self-awareness. Allport G. Formation of personality. Selected works. / Per. from English. - M., 2012. P.298.

More important than searching for the past or the history of an organism is the simple question of what the individual intends or seeks to do in the future. The hopes, desires, ambitions, aspirations, plans of a person are all presented under the general name of "intentions", "intentions", and this shows one of the most characteristic differences between Allport and most modern personality theorists. One of the controversial claims of this theory is that what an individual is trying to do (it is believed that a person can talk about it) is the most important clue to understanding how a person behaves in the present. While other theorists look to the past as the key to unraveling the mystery of behavior in the present, Allport turns to what a person intends to do in the future. In this regard, a strong similarity with the positions of Alfred Adler and Carl Jung is obvious, although there is no reason to believe that they were directly influenced.

So far, we have considered the personality in terms of composition and have explored the dispositions that activate behavior in a broader sense. Consider the question of how these structures appear, and how the individual is represented at various stages of development. As is already clear from our discussion of functional autonomy, this theory suggests important differences between childhood and adulthood.

Let's start with the individual at birth. Allport believes the newborn is almost entirely the product of heredity, primitive drives and reflexes. He has not yet developed those distinctive features that will appear later as a result of interaction with the environment. Significantly, from Allport's point of view, the newborn does not have a personality. From birth, the child is endowed with certain constitutional and temperamental properties, but the realization of the possibilities contained in them is possible only as they grow and mature. In addition, he is able to respond through very specific reflexes, such as sucking and swallowing, to very limited types of stimulation. Finally, he exhibits general undifferentiated reactions, in which a large part of the muscular apparatus is involved.

How is the child activated or motivated with all this? Allport admits that initially there is a general flow of activity - it is the original source of motivated behavior. At this moment of development, the child is predominantly the product of segmental tensions and experiences of pain and pleasure. So, motivated by the need to minimize pain, to maximize pleasure, which is determined mainly by the reduction of visceral, particular tension, the child continues to develop.

Already in the first year of life, says Allport, the child begins to show distinctive qualities, differences in movement and expression of emotions, which tend to persist and merge into more mature forms of adaptation acquired later. Allport concludes that from at least the second half of the first year of life, the child begins to show distinctive features that seem to represent enduring personality attributes. However, he notes that "the first year of life is the least important for the individual - provided that there is no serious harm to health." Myers, D. Psychology. / Translation from English. - Mn., 2015. P.456.

The development process goes along different lines. Allport believes that various principles and mechanisms are adequate to describe the changes that occur between childhood and adulthood. He especially discusses differentiation, integration, maturation, imitation, learning, functional autonomy, extension of the self. He even acknowledges the explanatory role of psychoanalytic mechanisms and trauma, although these phenomena are not central to what he calls the normal personality.

So, we have: an organism, which at birth is biological, transforms into an individual, with a growing ego, an expanding structure of traits, in which future goals and claims germinate. Essential to this transformation is, of course, functional autonomy. This principle makes it clear that what originally only served biological purposes becomes a motive in its own right, directing behavior with all the force of the original drive. Largely in connection with this discontinuity between the early and late motivational structures of the individual, we have, in essence, two theories of personality.

2.2 Mature personality

Allport was the first to introduce the idea of a mature personality into psychology, noting that psychoanalysis never considers an adult as a truly adult. In his 1937 book, he devoted a separate chapter to the mature personality, formulating three criteria for personal maturity. The first criterion is the diversity of autonomous interests, the expansion of the "I". A mature personality cannot be narrow. The second is self-consciousness, self-objectification. He also includes here such a characteristic as a sense of humor, which, according to experimental data, correlates best with self-knowledge. The third criterion is the philosophy of life. A mature personality has its own worldview, in contrast to an immature personality. allport personality temperament disposition

In later works, he expands and supplements the list of these criteria, describing already 6 main parameters of a mature personality, which incorporate the first three. First, a psychologically mature person has wide boundaries of the Self. Mature people are interested not only in themselves, but also in something outside of themselves, actively participate in many things, have hobbies, are interested in political or religious issues, in what they consider significant. Allport does not mean situations when a person has nothing interesting in life outside of his hobby. Secondly, they have an inherent ability for close interpersonal relationships. In particular, Allport mentions friendly intimacy and sympathy in this connection. The friendly intimate aspect of relationships is the ability of a person to show deep love for family, close friends, not colored by possessive feelings or jealousy. Kjell K.S., Lindsay G. Theory of Personality. / Translated from English. - M., 2013. P. 411.

Empathy is reflected in the ability to be tolerant of differences in values and attitudes between oneself and other people. The third criterion is the absence of large emotional barriers and problems, good self-acceptance. These people are able to calmly relate to their own shortcomings and external difficulties, without reacting to them with emotional breakdowns; they know how to cope with their own conditions and, while expressing their emotions and feelings, they consider how it will affect others. The fourth criterion is that a mature person demonstrates realistic perception as well as realistic claims. He sees things as they are, not as he would like them to be. Fifth, a mature person demonstrates the ability for self-knowledge and a philosophical sense of humor - humor directed at oneself.

Allport was the first psychologist who spoke seriously about the role of humor in the personality. Sixth, a mature person has a whole philosophy of life. What is the content of this philosophy does not play a fundamental role - the best philosophy does not exist.

As Allport's student T. Pettigrew noted at the symposium in memory of Allport, the reason for these changes in the set of criteria for a mature personality was largely due to their joint trip to South Africa to study racial problems. There they saw people who fit Allport's original definition of a mature person, but who did evil regularly and routinely. Allport later openly admitted that he underestimated the role of sociocultural factors in the formation of personality. Kjell K.S., Lindsay G. Theory of Personality. / Translated from English. - M., 2013. P. 415.

Unlike many personologists whose theories are based on the study of unhealthy or immature personalities, Allport never practiced psychotherapy and did not believe that clinical observations could be used to build a theory of personality. He simply refused to believe that mature and immature people really have much in common. He realized that many personologists of his time could not even define a healthy personality and, what is worse, did not make any significant effort to describe it. So Allport began the long work of creating an adequate description of the healthy personality, or what he called the "mature personality."

Allport believed that the maturation of a person is a continuous, lifelong process of becoming. He also saw a qualitative difference between a mature person and an immature or neurotic person. The behavior of mature subjects is functionally autonomous and motivated by conscious processes. On the contrary, the behavior of immature individuals is predominantly driven by unconscious motives stemming from childhood experiences. Allport concluded that a psychologically mature person is characterized by six features. Belinskaya E.P. Temporal aspects of I - concepts and identities. // World of psychology. - 2015. - No. 3. - P.142.

A mature person has wide boundaries of the Self. Mature individuals can look at themselves "from the outside." They are actively involved in work, family and social relationships, have hobbies, are interested in political and religious issues and everything that they consider significant. Such activities require the participation of the true self of the person and genuine passion. According to Allport, self-love is an indispensable factor in the life of every individual, but it does not have to be decisive in his lifestyle.

A mature person is capable of warm, cordial social relationships. There are two types of warm interpersonal relationships that fall under this category: friendly closeness and empathy. The friendly-intimate aspect of a warm relationship is manifested in a person's ability to show deep love for family and close friends, untainted by possessiveness or jealousy. Empathy is reflected in the ability of a person to be tolerant of differences (in values or attitudes) between himself and others, which allows him to demonstrate deep respect for others and recognition of their position, as well as commonality with all people.

A mature person demonstrates emotional unconcern and self-acceptance. Adults have a positive self-image and thus are able to tolerate both disappointing or irritating phenomena and their own shortcomings without becoming internally embittered or hardened. They are also able to manage their own emotional states (such as depression, anger, or guilt) in a way that does not interfere with the well-being of others. For example, if they're having a bad day, they don't lash out at the first person they meet. And what's more, when expressing their opinions and feelings, they take into account how it will affect others. Allport G. Formation of personality. Selected works. / Per. from English. - M., 2012. P.334.

A mature person demonstrates realistic perceptions, experiences and claims. Mentally healthy people see things as they are, not as they would like them to be. They have a healthy sense of reality: they do not perceive it distortedly, they do not distort the facts for the sake of their imagination and needs. Moreover, healthy people have the appropriate qualifications and knowledge in their field of activity. They may temporarily take a back seat to their personal desires and impulses until important business is completed. To convey the meaning of this aspect of maturity, Allport quotes renowned neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing: "The only way to prolong life is to have a task in front of you that you absolutely must complete." Thus, adults perceive other people, objects, and situations as they really are; they have enough experience and skill to deal with reality; they strive to achieve personally meaningful and realistic goals.

A mature person demonstrates the ability for self-knowledge and a sense of humor. Socrates noted that in order to live a fulfilling life, there is one paramount rule: "Know thyself." Allport called it "self-objectification". By this he meant that mature people have a clear idea of their own strengths and weaknesses. An important component of self-knowledge is humor, which prevents pompous self-aggrandizement and empty talk. It allows people to see and accept the extremely absurd aspects of their own and others' life situations. Humor, as Allport saw it, is the ability to laugh at the one you love the most (including your own person) and yet still appreciate it. Allport G. Formation of personality. Selected works. / Per. from English. - M., 2012. P.348.

A mature person has a whole philosophy of life. Mature people are able to see the whole picture through a clear, systematic and consistent selection of significant in their own lives. Allport believed that one should not be Aristotle and try to formulate an intellectual theory of the meaning of life. Instead, a person simply needs a value system that contains the main goal or theme that will make his life meaningful. Different people can form different values around which their life will purposefully be built. They can choose the pursuit of truth, social welfare, religion, or something else - according to Allport, the best goal or philosophy does not exist here. Allport's point of view on this matter is that the adult personality has a set of certain values deeply rooted in a person, which serve as the unifying basis of his life. A unifying philosophy of life therefore provides a kind of dominant value orientation that gives meaning and meaning to almost everything a person does.

Zakllearning

Gordon Allport was a unique, active, integrated, mature, forward looking individual. He left us the psychology of a unique, active, integrated, mature, future-oriented personality. Perhaps the most remarkable feature of Allport's theoretical writings is that, despite their pluralism and eclecticism, they generated a sense of novelty and found wide influence. Unlike many theorists, Allport did not leave a school of followers, although his influence can be found in the writings of former students. For the most part, his theory was developed by himself, and this lasted for almost half a century, starting with his interest in a unit adequate to describe a person. This led to the concept of traits, and subsequent work on the transformation of developing motives. This theory has presented interest to psychoanalysts.

Allport's emphasis on active propriative functions (ego functions) and the concept of functional autonomy are highly congruent with recent developments in psychoanalytic ego psychology. Thus, despite being one of the most intransigent critics of orthodox psychoanalysis, Allport eventually proved to be one of the most fashionable personality theorists among psychoanalysts. Another novelty of Allport's position is his emphasis on the importance of the conscious determinants of behavior and, accordingly, his defense of direct methods of investigating human motivation. More in line with modern trends in psychology is Allport's fervent appeal to study individual cases. Allport is one of the few psychologists who has bridged the gap between academic psychology with its traditions on the one hand and the rapidly developing field of clinical and personality psychology on the other.

Allport believed that the maturation of a person is a continuous, lifelong process of becoming. He also saw a qualitative difference between a mature person and an immature or neurotic person. The behavior of mature subjects is functionally autonomous and motivated by conscious processes. A mature person has wide boundaries of the Self. Mature individuals can look at themselves "from the outside." They are actively involved in work, family and social relationships, have hobbies, are interested in political and religious issues and everything that they consider significant. Such activities require the participation of the true self of the person and genuine passion. According to Allport, self-love is an indispensable factor in the life of every individual, but it does not have to be decisive in his lifestyle. A mature person is capable of warm, cordial social relationships. A mature person demonstrates emotional unconcern and self-acceptance. A mature person demonstrates realistic perceptions, experiences and claims. Mentally healthy people see things as they are, not as they would like them to be. They have a healthy sense of reality: they do not perceive it distortedly, they do not distort the facts for the sake of their imagination and needs. Moreover, healthy people have the appropriate qualifications and knowledge in their field of activity.

List of used literature

1. Abulkhanova-Slavskaya K.A. Life strategy M.: Thought, 2011. - 240p.

2. Belinskaya E.P. Temporal aspects of I - concepts and identities. // World of psychology. - 2015. - No. 3. - P.141-145.

4. Maklakov A.G. General psychology. St. Petersburg: Peter, 2015. - 583s.

5. Martsinkovskaya T.D. History of psychology. M.: Academy, 2014. - 538s.

6. Allport G. Formation of personality. Selected works. / Per. from English. - M.: Meaning, 2012. - 480s.

7. Petrovsky A.V., Yaroshevsky M.G. History and theory of psychology. Rostov n./D.: Phoenix, 2013. - 646 p.

8. Reinvald N.I. Psychology of Personality. M.: Publishing House of UDN, 2015. - 500p.

9. Stepanov S.S. Age of psychology: names and fates. M.: Eksmo, 2012. - 592s.

10. Fernhem A., Haven P. Personality and social behavior. St. Petersburg: Peter, 2013. - 368s.

11. Kjell K.S., Lindsay G. Theory of personality. / Translated from English. - M.: EKSMO-PRESS, 2013. - 592 p.

Hosted on Allbest.ru

...Similar Documents

R. Kettel's theory of personality traits. "Sixteen Personal Factors". Personality traits, predictable psychological characteristics. Hans Eysenck's theory of personality types. Psychology of personality in the theory of G. Allport. "Man is an objective reality."

abstract, added 09/29/2008

History and prerequisites for the formation of psychodynamic theories of personality, their prominent representatives and followers, fundamental ideas. Humanistic torii of personality E. Fromm. Personality theories of G. Allport and R. Cattell, their study of personality traits.

abstract, added 08/09/2010

Theories of personality. Dispositional theory of personality. Five-factor model of personality. Factor theories of personality. Factor theory of Cattell. Eysenck's theory. The theory of J.P. Guildford. "Motivational" concept (D.K. McClelland). Techniques for the study of the object.

term paper, added 06/03/2008

In his first book, Personality: A Psychological Interpretation, Allport described and classified over 50 different definitions of personality. The concept of personality traits. Proprium is self-development. Intentions. functional autonomy. Stages of personality development.

term paper, added 05/15/2008

Psychoanalytic theory of personality. E. Fromm's concept of personality. Cognitive direction in personality theory: D. Kelly. Humanistic theory of personality. Phenomenological direction. Behavioral theory of personality.

abstract, added 06/01/2007

Features of the relationship between the individual and society. The formation and development of personality is a problem of modern psychology and sociology. Role concept of personality. Psychoanalytic theory of personality Z. Freud. Cultural and historical concept of personality.

thesis, added 22.08.2002

Theoretical analysis of the problem of personality traits and types in Eysenck's theory. Basic concepts and principles of Eysenck's theory of personality types. Basic personality types. Measurement of personality traits. Diagnostic study of personality traits and types according to the Eysenck method.

term paper, added 01/19/2009

Personality and its characteristics. Temperament as a personality trait. Mentality as an ethnopsychological sign of a nation. Features of cross-cultural studies of personality. Cultural differences in self-esteem. Features of ethnopsychological personality traits.

term paper, added 08/09/2016

Personal development. Driving forces and conditions for the development of personality. An approach to understanding the personality in the school of A.N. Leontiev. Personality theory V.A. Petrovsky. An approach to understanding the personality in the school of S.L. Rubinstein. Theories of personality V.N. Myasishchev and B.G. Ananiev.

abstract, added 10/08/2008

Features differences in the everyday use of the word "personality". Analysis of the distinctive features of personality theory. The principle and essence of an adequate theory of psychotic behavior. General characteristics of the theory of behavior. The main questions of the modern theory of personality.

Gordon Willard Allport (November 11, 1897 – October 9, 1967) was an American psychologist and personality trait theorist.

Gordon Willard Allport (November 11, 1897 – October 9, 1967) was an American psychologist and personality trait theorist.

The Concept of Personality Allport suggested that one could briefly define personality as "what a person really is". However, agreeing that this definition is too short to be useful, he came to a more well-known one: "Personality is the dynamic organization of those psychophysical systems in the individual that determine his unique adaptation to the environment." The combination "dynamic organization" emphasizes that the personality is constantly changes and develops, although at the same time there is an organization or system that links together and correlates the various components of the personality. The term "psychophysical" recalls that the personality is "neither exclusively mental nor exclusively nervous." Organization involves the action of both the body and the psyche, inextricably linked in the unity of the individual. The word "determine" makes it clear that personality includes determining tendencies that play an active role in individual behavior. "Personality is something and does something ... It is what lies behind specific acts and within the individual"

The Concept of Personality Allport suggested that one could briefly define personality as "what a person really is". However, agreeing that this definition is too short to be useful, he came to a more well-known one: "Personality is the dynamic organization of those psychophysical systems in the individual that determine his unique adaptation to the environment." The combination "dynamic organization" emphasizes that the personality is constantly changes and develops, although at the same time there is an organization or system that links together and correlates the various components of the personality. The term "psychophysical" recalls that the personality is "neither exclusively mental nor exclusively nervous." Organization involves the action of both the body and the psyche, inextricably linked in the unity of the individual. The word "determine" makes it clear that personality includes determining tendencies that play an active role in individual behavior. "Personality is something and does something ... It is what lies behind specific acts and within the individual"

Personality structure According to Allport's theory, the two main components of personality are personal dispositions (such unique individual behaviors that are consistently repeated in a given person, but are absent in the vast majority of other people) and proprium. The use of these structures makes it possible to describe personality in terms of individual characteristics. The third component of personality is the conscious personality, or subjective personality.

Personality structure According to Allport's theory, the two main components of personality are personal dispositions (such unique individual behaviors that are consistently repeated in a given person, but are absent in the vast majority of other people) and proprium. The use of these structures makes it possible to describe personality in terms of individual characteristics. The third component of personality is the conscious personality, or subjective personality.

G. Allport distinguished three types of personal dispositions: cardinal, central and secondary. Cardinal dispositions are the most generalized, all-pervading personality trait that determines a person’s entire life. It is endowed with very few people who, as a rule, become widely known precisely because of the presence of a cardinal disposition. Moreover, the names of these people become common nouns for a certain lifestyle or behavioral strategies, for example, Don Juan, Thomas the Unbeliever, the Marquis de Sade, etc. Central dispositions are stable characteristics that are well recognized by other people, allowing you to fully and accurately describe a person. Based on the results of his research, G. Allport came to the conclusion that the number of central dispositions for each individual varies from five to ten. The central dispositions are the most universal and, in terms of content, are close to personality traits. Secondary dispositions are less stable and less recognizable compared to the central ones. These usually include taste preferences, situational short-term attitudes, etc.

G. Allport distinguished three types of personal dispositions: cardinal, central and secondary. Cardinal dispositions are the most generalized, all-pervading personality trait that determines a person’s entire life. It is endowed with very few people who, as a rule, become widely known precisely because of the presence of a cardinal disposition. Moreover, the names of these people become common nouns for a certain lifestyle or behavioral strategies, for example, Don Juan, Thomas the Unbeliever, the Marquis de Sade, etc. Central dispositions are stable characteristics that are well recognized by other people, allowing you to fully and accurately describe a person. Based on the results of his research, G. Allport came to the conclusion that the number of central dispositions for each individual varies from five to ten. The central dispositions are the most universal and, in terms of content, are close to personality traits. Secondary dispositions are less stable and less recognizable compared to the central ones. These usually include taste preferences, situational short-term attitudes, etc.

Allport proposes to call all the functions of the Ego and I the own functions of the personality. All of them (including body feeling, identity, self-respect, self-extension, sense of self, rational thinking, self-image, one's aspirations, cognitive style, cognitive function) are real and vital parts of the personality. They have in common - a phenomenal "warmth" and "sense of significance." We can say that together they cover "own" (proprium).

Allport proposes to call all the functions of the Ego and I the own functions of the personality. All of them (including body feeling, identity, self-respect, self-extension, sense of self, rational thinking, self-image, one's aspirations, cognitive style, cognitive function) are real and vital parts of the personality. They have in common - a phenomenal "warmth" and "sense of significance." We can say that together they cover "own" (proprium).

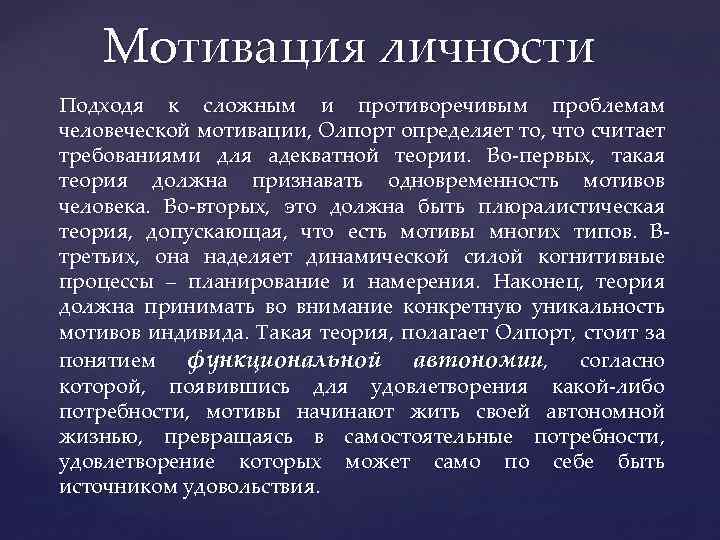

Personal Motivation Approaching the complex and controversial problems of human motivation, Allport defines what he considers the requirements for an adequate theory. First, such a theory must recognize the simultaneity of human motives. Second, it must be a pluralistic theory, admitting that there are many types of motives. Third, it gives dynamic power to cognitive processes—planning and intentions. Finally, the theory must take into account the specific uniqueness of the individual's motives. Such a theory, Allport believes, is behind the concept of functional autonomy, according to which, having appeared to satisfy a need, motives begin to live their own autonomous life, turning into independent needs, the satisfaction of which can in itself be a source of pleasure.

Personal Motivation Approaching the complex and controversial problems of human motivation, Allport defines what he considers the requirements for an adequate theory. First, such a theory must recognize the simultaneity of human motives. Second, it must be a pluralistic theory, admitting that there are many types of motives. Third, it gives dynamic power to cognitive processes—planning and intentions. Finally, the theory must take into account the specific uniqueness of the individual's motives. Such a theory, Allport believes, is behind the concept of functional autonomy, according to which, having appeared to satisfy a need, motives begin to live their own autonomous life, turning into independent needs, the satisfaction of which can in itself be a source of pleasure.