The settlement of Mesopotamia began in ancient times due to the resettlement of the inhabitants of the surrounding mountains and foothills to the river valley and noticeably accelerated in the Neolithic era. First of all, Northern Mesopotamia, which was more favorable in terms of natural and climatic conditions, was developed. The ethnicity of the carriers of the most ancient (preliterate) archaeological cultures (Hassun, Khalaf, etc.) is unknown.

Somewhat later, the first settlers appeared in the territory of Southern Mesopotamia. The most vibrant archaeological culture of the last third of the 5th - first half of the 4th millennium BC. e. represented by excavations at Al-Ubeid. Some researchers believe that it was created by the Sumerians, others attribute it to pre-Sumerian (proto-Sumerian) tribes.

We can confidently state the presence of the Sumerian population in the extreme south of Mesopotamia after the appearance of writing at the turn of the 4th - 3rd millennia BC. e., but the exact time of the appearance of the Sumerians in the Tigris and Euphrates valley is still difficult to establish. Gradually, the Sumerians occupied a significant territory of Mesopotamia, from the Persian Gulf in the south to the point of greatest convergence of the Tigris and Euphrates in the north.

The question of their origin and the family ties of the Sumerian language remains highly controversial. At present, there are no sufficient grounds to classify the Sumerian language as belonging to one or another known language family.

The Sumerians came into contact with the local population, borrowing from them a number of toponymic names, economic achievements, some religious beliefs,

In the northern part of Mesopotamia, starting from the first half of the 3rd millennium BC. e., and possibly earlier, lived East Semitic pastoral tribes. Their language is called Akkadian. It had several dialects: Babylonian was widespread in southern Mesopotamia, and the Assyrian dialect was widespread to the north, in the middle part of the Tigris Valley.

For several centuries, the Semites coexisted with the Sumerians, but then began to move south and by the end of the 3rd millennium BC. e. occupied all of Mesopotamia. As a result, the Akkadian language gradually replaced Sumerian. By the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC. e. Sumerian was already a dead language. However, as a language of religion and literature, it continued to exist and be studied in schools until the 1st century. BC e. The displacement of the Sumerian language did not at all mean the physical destruction of its speakers. The Sumerians merged with the Semites, but retained their religion and culture, which the Akkadians borrowed from them with only minor changes.

At the end of the 3rd millennium BC. e. from the west, from the Syrian steppe, West Semitic cattle-breeding tribes began to penetrate into Mesopotamia. The Akkadians called them Amorites. In Akkadian, Amurru meant “Syria”, as well as “west” in general. Among these nomads there were many tribes who spoke different but closely related dialects. At the end of the 3rd - first half of the 2nd millennium, the Amorites managed to settle in Mesopotamia and found a number of royal dynasties.

Since ancient times, Hurrian tribes have lived in Northern Mesopotamia, Northern Syria and the Armenian Highlands. The Sumerians and Akkadians called the country and tribes of the Hurrians Subartu (hence the ethnic name Subarea). In terms of language and origin, the Hurrians were close relatives of the Urartian tribes who lived on the Armenian Highlands at the end of the 2nd-1st millennia BC. e. The Hurrians lived in certain areas of the Armenian Highlands back in the 6th-5th centuries. BC e.

Since the 3rd millennium, in North-Eastern Mesopotamia, from the headwaters of the Diyala River to Lake Urmia, there lived semi-nomadic tribes of the Kutians (Gutians), whose ethnic origin still remains a mystery, and whose language differs from Sumerian, Semitic or Indo-European languages. It may have been related to Hurrian. At the end of the XXIII century. Kutni invaded Mesopotamia and established their dominance there for a whole century. Only at the end of the XXII century. their power was overthrown, and they themselves were thrown back to the upper reaches of Diyala, where they continued to live in the 1st millennium BC. e.

Since the end of the 3rd millennium, in the foothills of the Zagros, next to the Gutians, lived the Lullubi tribes, which often invaded Mesopotamia, about whose origin and linguistic affiliation nothing definite can yet be said. It is possible that they were related to the Kassite tribes.

The Kasites lived in Northwestern Iran, north of the Elamites, from ancient times. In the second quarter of the 2nd millennium BC. e. Part of the Kassite tribes managed to establish themselves in the valley of the Diyala River and from there carried out raids into the depths of Mesopotamia. At the beginning of the 16th century. they captured the largest of the Mesopotamian states, Babylonia, and founded their dynasty there. The Kassites who settled in Babylonia were completely assimilated by the local population and adopted their language and culture, while the Kassite tribes who remained in their homeland retained a native language different from Sumerian, Semitic, Hurrian and Indo-European languages.

In the second half of the 2nd millennium BC. e. A large group of West Semitic Aramean tribes moved from Northern Arabia to the Syrian steppe and further to Northern Mesopotamia. At the end of the 13th century. BC e. they created many small principalities in Western Syria and Southwestern Mesopotamia. By the beginning of the 1st millennium BC. e. they almost completely assimilated the Hurtite and Amorite populations of Syria and ancient Mesopotamia. The Aramaic language began to spread widely and firmly beyond this territory.

After the conquest of Babylonia by the Persians, Aramaic became the official language of the state chancellery of the entire Persian state. Akkaden was preserved only in large Mesopotamian cities, but even there it was gradually replaced by Aramaic and by the beginning of the 1st century. BC h. was completely forgotten. The Babylonians gradually merged with the Chaldeans and Arameans. The population of Ancient Mesopotamia was heterogeneous, due to the policy of forced resettlement of peoples, which was carried out in the 1st millennium BC. e. in the Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian powers, and the strong ethnic circulation that took place in the Persian power, which included Mesopotamia.

Slavery in Ancient Mesopotamia had specific features that distinguished it from the classical one. On the one hand, here free people bore a heavy burden of duties to the state or householder. The latter had the right to force household members to work, to marry off young women for ransom, and in some cases even to force his wife into slavery. Household members found themselves in the worst position when the householder exercised his right to use them as collateral for a loan. With the development of commodity-money relations, freedom began to be limited by various forms of legalized bondage into which the insolvent borrower fell. On the other hand, slaves here had certain rights and freedoms. Giving slaves legal personality turned out to be a kind of institutional counterbalance to the ease with which a full-fledged person could lose his freedom. But not least of all, this became possible because in the community of full-fledged people of Mesopotamia the prevailing idea was of a slave not as a thing or a socially humiliated agent, but primarily as a source of constant income. Therefore, in practice, in most cases, the exploitation of slaves in Mesopotamia acquired soft, almost “feudal” forms of collecting quitrents, and the slave himself often became the object of investment in human capital. Conducting an accurate usurious calculation of benefits and costs, the slave owners of Mesopotamia learned to turn a blind eye to class prejudices and see their benefit from providing the slave with broad economic autonomy and legal rights. The distance between freemen and slaves in Mesopotamia was further reduced by social institutions that provided vertical mobility, allowing people to move from one social class to another.

Keywords: slavery, Sumer, Akkad, Assyria, Babylonia, Mesopotamia, civil law relations, social structure, economic system.

Slavery in Ancient Mesopotamia was characterized by a peculiar feature that distinguished it from classic slavery. On the one hand, the free men carried a heavy burden of obligations to the government or patriarchal householder. They had the right to compel the family to work, to marry young women for ransom, and sometimes even pay wife into slavery. The worst situation was when a householder would exercise the right to use the family as collateral for a loan. When commodity-money relations developed, freedom became more restricted due to the introduction of several forms of legalized slavery of the bankrupts. On the other hand, slaves possess certain rights and freedoms. This became a kind of institutional counterweight to the easy enslavement of free people. However, this became possible because the Mesopotamian community considered slaves not as things, but mostly as resources of a steady income. Therefore, in practice the exploitation of slaves in Mesopotamia mostly acquired a soft, almost “feudal” form of collection of dues, and the servant was often the target of investment in human capital. Slave-owners in Mesopotamia would keep an accurate calculation of costs and benefits, and thus learned to disregard some class prejudice, and to perceive the benefits from providing a slave with a broad economic autonomy and legal rights. The distance between free and slaves in Mesopotamia declined even more due to the activity of social institutions, which provided vertical mobility for people to move from one social class to another.

Keywords: slavery, Sumer, Akkad, Assyria, Babylonia, Mesopotamia, civil relations, social structure, economic system.

According to the prevailing principles in the 19th century. views, the social organization of societies of the Ancient World was fundamentally based on common principles. They were formulated during the analysis of ancient societies that had been well studied by that time and assumed the existence of irreconcilable and irremovable contradictions between the two main classes of the slave-owning formation - slave owners and slaves. The former were endowed with the right of ownership of the means of production and the slaves themselves, while the latter, although they were the main productive force of society, were deprived not only of property, but also of any rights at all (Philosophical... 1972: 341).

This paradigm quite correctly characterized the social relations that existed in Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome, as well as in the states that fell into the orbit of their economic and cultural influence. However, today it is unlikely that any specialist would risk asserting that it was equally adequate in relation to the societies of the Ancient East.

Doubts about the heuristic value of a single nomothetic approach to understanding slavery in the west and east of Eurasia were expressed almost immediately after its emergence, and were formulated in its final form by Karl August Wittfogel (Wittfogel 1957). As he expanded and studied historical material, his hypothesis about the uniqueness of the Asian mode of production found more and more confirmation. In particular, in recent decades, in the course of historiographical, anthropological and sociological research, results have been obtained that make it possible to judge the blurring of the boundaries between the main classes in the slave states of Ancient Asia. It turned out that here they were not at all separated by the social gulf that lay between them on the pages of books outlining ideal-typical ideas about ancient slavery, and the severity of the contradictions between classes was dampened by state legislation designed to ensure social peace and order.

A good addition to the overall picture illustrating the features of slavery in the Ancient East could be a description of the social practices that developed between the state, free people and slaves in the societies of Mesopotamia - Sumer, Akkad, Assyria and Babylonia.

Considering the economic cultures of these societies as parts of a single economic and cultural complex, it is easy to see that an invariant feature of the class structure of Ancient Mesopotamia is the presence in it, in addition to a layer of those partially endowed with rights (Sumer. shub-lugal or Akkadian miktum And mush-kenum), two opposite poles - full-fledged free people, called “people” (Akkad. avilum), on the one hand, and slaves, on the other. In addition, one can find that free people here bore a heavy burden of duties, slaves had certain rights and freedoms, and social institutions ensured the existence of corridors of vertical mobility that allowed people to move from one social class to another.

Thus, analyzing the situation of free community members in Mesopotamia, we can come to the conclusion that they could not fully enjoy the privilege of their social position.

It is well known that among other classes, free community members had the greatest number of rights. First of all, they were endowed with the right to use land plots and the ability to dispose of them. This possibility of theirs was interpreted by some researchers even as a manifestation of the private property rights of community members to land (Shilyuk 1997: 38–50; Suroven 2014: 6–32), which they may not have actually possessed. Despite the discussions surrounding the issue of ownership of land by full free people, today it is generally accepted that they had the right to own, use and dispose of other real estate, as well as movable property. In addition, in a critical situation, they could count on emergency government support, forgiveness of debts to private individuals and, with the exception of later periods, even write-off of arrears to the state. These rights were legislatively enshrined in the Laws of Uruinimgina (I, art. 1–9, II, art. 1–11), the laws of Lipit-Ishtar (art. 7, 9, 12–19, 26–32, 34, 36–43 ), Middle Assyrian laws, Table B + O, laws of Hammurabi (vv. 4, 7, 9–13, 17–18, 25, 42, 44, 46–56, 64–66, 71, 78, 90, 99, 112 –116, 118, 120–125, 137–139, 141–142, 146–147, 150–152, 160–164), etc.

Having a significant amount of powers and freedoms, full-fledged community members were not free from very burdensome obligations, and above all in relation to the state.

Thus, in Sumer they were required to serve four months of the year as laborers on irrigation work and cultivating temple lands. At the same time, the administration of the temples vigilantly ensured that the community members fully fulfilled their duties. For this purpose, temple officials carefully monitored the working time spent, adjusted to take into account the worker’s ability to work.

For these purposes, each of them was assigned a working capacity coefficient, calculated in shares of the labor force. The resolution of the work ability scale was very high. Usually, full-time and half-time workers were distinguished, but in the cities of Nippur and Puprizhgan there is also a “subtle” differentiation of the worker’s ability to work - in 1, 2/3, 1/2, 1/3 and 1/6 of the labor force (World... 1987: 52 –53). Community members who paid their debt in full, as well as temple personnel, received in-kind and cash allowances from state storage facilities, which was also reflected in the reporting. According to it, food was distributed to workers in most cases on a monthly basis.

Those serving conscription received food rations, which included grain, fish, bread, vegetable oil, dates, beer, as well as non-food items - fabric or wool for clothing and even some silver, which was used in Sumer as a means of payment (World... 1987: 53) . The amount of remuneration was also determined by the quantity and quality of labor expended. In Lagash, for example, there were three categories of food ration recipients: lu-kur-dab-ba– “people receiving food” (skilled workers); igi-nu-du– “people receiving separate plates” (unskilled workers); gim-du-mu– “slaves and children”, including nu-sig- “orphans”. Similarly, in Ur, in addition to full-time workers, food was received by: dum-dumu- "half-time workers" bur-su-ma- “old people”, as well as “bread eaters” (Tyumenev 1956). In order to ensure uninterrupted work on the formation of public consumption funds and the reproduction of the labor force, temple officials had the right to apply sanctions against those who evaded the conscientious performance of their duties to the state. There is reason to believe that draft dodgers were obliged to compensate the state for lost labor in an amount equal to “the average wage, i.e., the wage that had to be paid to those hired to replace workers who did not show up for any reason at public work" (Kozyreva 1999: 48).

With the development of means of production, the temple farming system began to degrade. Even during the reign of the III dynasty of Ur, lands gradually began to be alienated from temples and transferred to free people as awards for service or for conditional lifetime use. With the fall of the dynasty, centralized temple economies practically ceased to exist. But it can hardly be said that with the abolition of the centralized planned economy, ordinary community members of Mesopotamia became freer. Some forms of addiction have been replaced by others.

Indeed, the elimination of the monopoly of temples on the disposal of resources contributed to the expansion of the sphere of commodity-money relations and the development of the economic institutions of purchase and sale and temporary transfer of rights to property, lease, sublease, credit, pledge and guarantee that provided them. Often, as a result of the unfavorable outcome of market transactions, people found themselves in extremely difficult situations, losing their property and even, in whole or in part, their freedom. This inevitably led to the emergence of a large class of people who were partially or completely deprived of their rights and became dependent on the new owners of the means of production - the state and private individuals (Kechekian 1944).

The state has repeatedly made attempts to regulate private law relations in order to protect “people” from moneylenders, for which it legislatively established the terms of trade and even prices for basic goods and services, as well as the terms of credit, hiring, rent, etc. This is reflected in laws King Eshnunna (XX century BC), the laws of Lipit-Ishtar (XX–XIX centuries BC), the laws of Hammurabi (XVIII century BC) (History... 1983: 372–374 ). These measures, of course, restrained the process of property and social stratification in Mesopotamia and contributed to the fact that a fairly significant layer of free people remained in society. But even they could not help but feel the pressure of social and economic pressure.

One of the most vulnerable categories of the free population of Ancient Mesopotamia were members of the family of the patriarchal householder.

For example, according to the Laws of Hammurabi, the latter had the right to force them to work, to marry young women for ransom, and even to enslave his wife, if she caused damage to the household with her preparations for divorce (Article 141). But the households were probably in the worst position in the case where the householder exercised his right to use them as security for a loan and entered into an agreement on this matter with the lender (Grice 1919: 78). This happened if the head of the family was unable to repay the debt to his creditor. Using a hostage in this way, the householder had the right either to sell him to a third party with the subsequent transfer of the proceeds to the creditor (Articles 114–115), or to transfer a member of his family directly to the lender into bondage to pay off his obligations (Article 117). In both cases, the debtor was considered freed from his obligations, but at the cost of the freedom of his family member.

It is important to note, however, that the state did not leave the hostage alone with his new owners, but actively interfered in their relations.

First of all, the code prohibited the creditor from using the debtor’s difficult life situation for selfish purposes. According to Art. 66, “if a person took money from a tamkar and this tamkar presses him, and he has nothing with which to pay the debt, and he gave his garden to the tamkar after pollination and said to him: “The dates, how many of them there are in the garden, you will take for your silver,” then tamkar must not agree; only the owner of the garden must take the dates, how many of them there will be in the garden, and the silver with its interest, according to his document, he must pay tamkara, and only the owner of the garden must take the rest of the dates that will be in the garden” (Chrestomatiya... 1980: 138) . As can be seen from the text of the article, the law provides the debtor with a deferment in repaying the debt and prohibits the lender from seizing the debtor’s crop in excess of the cost of the loan with interest. Obviously, this norm was intended to limit the process of impoverishment of free, full-fledged people and their loss of their high social position as a result of self-selling into slavery or being taken hostage for debts.

However, if this did happen and a free person became dependent on a creditor, then, according to the Code of Hammurabi, he was not deprived of legal protection from ill-treatment. It was defined by Art. 196–211 and established the degree of responsibility of a person depending on the degree of damage to the physical condition that he caused to another full-fledged person, as well as to a person affected in terms of his rights - a muskenum and even a slave.

Thus, if a person lost an eye due to ill-treatment, then his offender also had to have his eye gouged out (Article 196). Similarly, for a broken bone, the offender of equal status was punished with a broken bone (Article 197), for a knocked out tooth he was deprived of a tooth (Article 200), for a blow to the cheek he was obliged to pay a fine of 1 mina of silver (Article 203), for an unintentional inflicting harm to health, he had to swear: “I hit unintentionally” - and pay the doctor (Article 206), but if as a result of beating an equal died, then the fine was already 1/2 mina of silver (Article 207). But for intentionally causing death, the Code of Hammurabi provided for a more severe punishment than fines or the implementation of the principle of talion for minor damage. Thus, by causing the death of a woman as a result of beatings, the perpetrator doomed his daughter to death (Article 210), and Art. 116 of the Code directly determines that “if a hostage died in the house of the mortgagee-lender from beatings or ill-treatment, then the owner of the hostage can incriminate his tamkar, and, if this is one of the full-fledged people, the lender’s son must be executed...” (Chrestomathy... 1980 : 161).

The fundamental point of the Old Babylonian legislation is that it not only protected the hostage from ill-treatment, but also determined the maximum period for his stay in servitude to the buyer or creditor. According to Art. 117 “if debt overcomes a person and he sells his wife, his son and his daughter for silver or gives them into bondage, then for three years they must serve the house of their buyer or their enslaver, in the fourth year they must be given freedom” (Ibid. : 161). It is important to note that this norm not only established the time frame for the social dependence of a full-fledged person, but also limited the process of property differentiation. After all, knowing the maximum terms of exploitation of the hostage’s labor, a rational lender was forced to limit the amount of the loan, thereby increasing the debtor’s chances of repaying it. As a result, a significant number of full-fledged free people remained in society, and capital owners did not have the opportunity to unlimitedly enrich themselves through usurious transactions.

It should be noted, however, that with the development of commodity-money relations, the legislative rights of the creditor were expanded. For example, the Middle Assyrian laws of the second half of the 2nd millennium BC. e., discovered at the beginning of the 20th century. during excavations in Ashur and which have come down to us in the form of tablets from A to O, good treatment of a hostage is no longer used as an absolute imperative, as it was in the Code of Hammurabi. Table A of the Assurian laws states that "if an Assyrian or Assyrian woman living in a man's house as collateral for their price is taken for full price, then he (the lender) may beat them, pull them by the hair, damage or pierce their ears" ( Reader... 1980: 201). As can be seen, legal protection against mistreatment in bondage extended only to people taken hostage whose value was assessed above the value of the loan. If this condition was not met, the lender had the right to force the hostage to work using physical force. It is also significant that the Ashur laws did not even contain any mention of limiting the duration of a hostage’s stay in the lender’s house, in fact allowing for his lifelong enslavement.

Babylonian laws further increased the lack of rights of household members. They removed the restrictions apparently established by Hammurabi on the right of a householder to dispose of his family members at his own discretion. If the Code of Hammurabi allowed the sale or enslavement of a household member solely in the form of payment of an existing debt (Articles 117, 119), then in Babylon in the 7th–6th centuries. BC, the practice of selling family members for the sake of enrichment had already become widespread. This is evidenced by the texts of contracts on the sale and purchase of slaves. In one of them, for example, it is stated that the Assyrian woman Banat-Innin announced in the national assembly and in the presence of the state property distributor that she remained a widow and, due to her poor situation, “branded her young children Shamash-ribu and Shamash-leu and gave them to the goddess (that is, to the temple. - S. D.) Belit of Uruk. While they are alive, they will truly be temple slaves of Belit Uruk” (Yale... 1920: 154).

Having reduced the level of protection for an insolvent debtor and a member of a patriarchal family, Assyrian society nevertheless developed practices for their social rehabilitation. The most common among them are “revival” and “adoption”.

The practice of "revival in distress" involved an insolvent father giving his daughter to the "revivalist." The latter accepted the “revived” one for feeding and received the right to use her labor force in his household until she was bought back at full price by her own father. In addition, the “reviver” received the right to marry off the girl, which could be considered by him as a profitable commercial enterprise, since according to the rule that existed among the Assyrians, he received a property ransom from the future husband - a “marriage gift.” But the reasons for the girl’s own father were obvious in this case: for handing over his daughter to the “reviver,” he received a monetary reward and retained her status as a full-fledged Assyrian (Dyakonov 1949).

Like “revival,” “adoption” was also the form in which the relationship between the creditor and the insolvent debtor was clothed. For example, according to the text of the treaty between the Assyrians Erish-ili and Kenya, the son of Erish-ili Nakidu was adopted by Kenya “with his field and his house and all his property. Nakidu is the son, Kenya is his father. In the field and inside the settlement, he (Nakidu) must work for him (Kenya). Nakidu like a father and Kenya like a son should treat each other. If Nakidu does not work for Kenya, without trial or dispute, he (Kenya) can shave him (Nakidu) and sell him for silver” (Chrestomatiya... 1980: 209). This document is obviously evidence of a pretended adoption by the lender of a family member of the debtor who is unable to fulfill his obligations under the loan. After all, its signatories did not forget to mention that the debtor’s son is adopted along with all his property, and they focus on the sanctions that awaited the “adopted” in the event of his refusal to work for the “adoptive parent.” But, as in the case of “revival,” this form of relationship between lender and debtor was beneficial to both parties. The creditor received at his disposal labor and property, as well as the unconditional right to dispose of the fate of the “adopted” at his own discretion, up to and including selling him into slavery. In turn, the debtor was released from his obligations under the loan and retained the status of a free person for his family member, whose full rights, under the terms of the agreement, were limited to no more than in his former family - by the patriarchal power of his new “father”.

One should not be surprised at the ingenuity that entitled people have shown in order to avoid debt slavery. The attitude towards slaves in Mesopotamia is well illustrated by how much the life and health of a slave were valued in comparison with the life and health of a free person.

For example, the legal principle of talion did not apply to slaves. If for causing physical defects to a free person the criminal received a symmetrical punishment, then when causing damage to a slave he got off with a fine of half his purchase price, and even that was paid not to the victim, but to his owner (Article 199). The death of a slave from ill-treatment in the house of the new owner threatened the latter not with the loss of his son, as would be punishable if the death of a full-fledged person was caused, but only with a fine of 1/3 of a mina of silver and the loss of the entire amount of the loan issued to the debtor (Article 161).

It is easy to see that the law valued the life and health of a slave lower than the life and health of a full and partial person. And yet, the position of the slave in Mesopotamia was incomparably higher than the position of the slave in the ancient states. This is evidenced by documents that reveal to us certain aspects of his social and legal status.

First of all, from Art. 175–176 of the Code of Hammurabi, it follows that slaves belonging to the state, as well as to non-full muskenums, had the right to marry representatives of any social class, as well as to have their own property and run their own household. In later times, the legislation of Mesopotamia completely removed obvious restrictions on these rights, granting them, apparently, to all slaves without exception.

The source of the formation of the property complex of slaves was not only their own funds, but probably also the funds of their masters. There are no direct indications of this. However, this can be judged by how carefully the slave owner, who viewed his slave as a reliable source of permanent income, treated his “property” and with what rationality he usually approached the formation of the slave’s ability to receive these incomes. The basis of this frugality was, most likely, simple economic calculation. As Douglas North showed in his work Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance, in some cases the marginal cost of controlling a slave was greater than the marginal benefit of his servitude. “In view of the increasing marginal costs of evaluation and control,” he wrote, “it is not profitable for the owner to establish comprehensive control over the slave’s labor, and he will exercise control only until the marginal costs equal the additional marginal revenue from controlling the slave. As a result, the slave acquires some property rights over his own labor. Masters can increase the value of their property by granting slaves some rights in exchange for those results of slave labor that the masters value most" (North 1997: 51).

It is no coincidence that slave exploitation in Mesopotamia appears to us in a soft, almost “feudal” form of collecting quitrent from a slave (Scheil 1915: 5), and investments in his human capital have become very widespread. For example, we have documentary evidence that free people paid for the training of their slaves in weaving (Strassmaier 1890: 64), baking ( Ibid.: 248), house-building (Petschow 1956: 112), leatherworking (Strassmaier 1892: 457), etc. It is easy to understand that during the training slaves acquired sought-after professions and were protected from the mistreatment of extreme forms of exploitation by the high qualifications of their labor .

Probably, in some situations, it was even more profitable for the slave owner to grant his slave freedom subject to the lifelong maintenance of his former master, rather than limit his freedom. There is also documentary evidence of this. Although it should be noted here that, when granting freedom to a slave, the owner, as a rule, did not forget to bind his former slave with obligations to “deliver him food and clothing,” and in case of failure to fulfill these obligations, he “broke”, that is, disavowed, the drawn up document on granting freedom freedman ( Idem 1889: 697).

This combination of “generosity” and prudence in relation to slaves is a sure indication that investments in the human capital of slaves and granting them freedom were not so much a manifestation of the humanism of slave owners as they expressed their desire to best provide for themselves materially. But in any case, it should be noted that the position of the slave in Mesopotamia was in many ways at odds with the image of a silent living instrument, crushed by the burden of backbreaking monotonous work, which is still attributed to him on the pages of some scientific publications. The importance of the slave in the socio-economic Ancient Mesopotamia was reinforced by his by no means insignificant legal status.

There is documentary evidence that since the time of Sumer, a slave had the right to independently appear in court, including with claims about the illegality of his stay in the status of a slave. The plaintiff usually addressed the judges with the words: “I am not a slave” - and tried to bring arguments established by law in support of his rights. As a rule, they were either signs that established or confirmed his status as a free person, or sworn testimony of witnesses (Chrestomatiya... 1980: 148–149).

This tradition was continued in Babylonia and Assyria. This is evidenced by both the texts of laws and the records of court hearings devoted to disputes over the legality of a slave’s stay in captivity. So, according to Art. 282 of the Laws of Hammurabi, a slave had the right to go to court to gain freedom, but had to convincingly argue his demands - otherwise the owner had the right to cut off his ear. Documents from later times serve as a good illustration of the fact that slaves were not afraid of possible punishment and boldly put forward claims against their masters. The numerous records of court hearings with similar disputes indicate that slaves had a chance to gain freedom through the courts. Here we can cite as an example the protocol of a lawsuit by a slave named Bariki - or to recognize him as free. When asked by the judges to present a document confirming his freedom, Bariki-ili replied: “I escaped twice from my master’s house, they didn’t see me for many days, I hid and said: “I am a free man.”<…>I am a free man, the guard of Bel-rimanni, who is in the service of Shamash-dimik, the son of Nabu-nadin-ah..." (Strassmaier 1890: 1113). The document may be of interest to us not only as direct evidence of the routinization of the practice of a slave challenging his status. From its context, it can be seen that Barika-ili's regime of captivity was such that it allowed him not only to escape, but to do so twice. It is also noteworthy that such actions of the slave remained without any harmful consequences for him. Indeed, despite his capture and return to his former master, he was not marked with lifelong markers of his slave status and tendency to escape, which allowed Shamash-dimik to accept him into service as a guard.

One must think that in the societies of Ancient Mesopotamia the sphere of legal personality of a slave was not limited only to his participation in trials regarding disputes regarding his status. It was much broader and was expressed not only in endowing the slave with such “formal” rights, such as, for example, the right to testify against his master without being subjected to bastonade (Chrestomatiya... 1980: 237), but also opened up for him certain opportunities to freely organize his relations with full rights on a mutually beneficial contractual basis.

The practice of slaves purchasing property from full-fledged slaves and even their participation in the creation of commercial enterprises on an equal basis with free people on the terms of an equal partnership became widespread. For example, according to an agreement between Bel-katsir, a descendant of a washerman, and the slave Mrduk-matsir-apli, concluded in 519 BC, each party contributed 5 mina of silver in order to organize trade, and also divided the proceeds from trade equally (Strassmaier 1892: 97). As can be seen in this case, the low social status of Mrduk-matsir-apli did not in any way affect his negotiating positions and did not reduce his share in the profits received.

It is important to note that in economic relations with free people, slaves could occupy an even higher position in relation to free people. This happened if their role as an economic agent turned out to be more significant in comparison with the economic role of a full-fledged person.

First of all, the slave was endowed with the right to provide a loan to a free person on the terms of payment of interest and to demand from the debtor the fulfillment of his obligations. For example, in 523 BC, the slave Dayan-bel-utsur provided Bariki-Adad, the son of Yahal, 40 hens of barley, 1 mina of silver and 3300 heads of garlic on the condition of receiving 40 hens of barley from the debtor every month, and in addition , “out of 1 mina of silver, ½ mina of silver (and) garlic Bariki-Adad must give to Dayan-bel-utsuru from his income” (Strassmaier 1890: 218). It is obvious that, taking on the role of a lender, the slave did this for the sake of obtaining material gain. And in this sense, it is important to note that his economic status was protected by a document issued to him with the signatures of a scribe, as well as witnesses certifying the legality and purity of the transaction. There is also no doubt that free people were forced to fulfill their obligations to the slave. This is evidenced by the texts of receipts issued by slave-lenders to their former debtors, stating that they received everything due under the contract and consider the relationship under it completed. An example of such a document is a receipt issued in 507 BC by the same slave Dayan-bel-utsur to another full-fledged one. It stated that “Dayan-bel-utsur, a slave belonging to Marduk-matsir-apli, a descendant of Egibi, received his debt, capital and interest from the hands of Kunnata, daughter of Akhhe-iddin, wife of Bel-iddin” ( Idem 1892: 400).

Babylonian slaves had the right not only to engage in usurious transactions, but also to act as tenants. At the same time, they could rent both the property of free people (The University... 1912: 118) and labor. First of all, a slave had the opportunity to exploit the labor power of another slave. An example is the agreement of 549 BC between Idti-marduk-balatu, the son of Nabu-ahhe-iddin, and the slave Ina-cilli-Belu, the slave of Ina-kiwi-Bela, in that the latter for rent He takes 9 shekels of silver for himself for a year and has the right to use the labor of the slave Idti-marduk-balata named Bariki-ili (Strassmaier 1889: 299).

However, the rights of the slave as an employer of labor were not limited to this. As surprising as it may seem to some of us, his rights extended to the sphere of hiring the labor of full-fledged Babylonians. For example, according to the agreement concluded in 532 BC, Zababa-shum-utsur, the son of Nabu-ukin-zer, hired out his son Nabu-bullitsu to the slave Shebetta for 4 shekels of silver per year, with the condition, however, that he continued to do work in his father's house for two months a year. Having signed the agreement, the parties, as equal participants in the transaction, “received one document each” (Strassmaier 1890: 278). The document gives no reason to think that Shebetta's obligation to grant the son of a free man leave to work in his father's house is a concession that she was forced to make by virtue of her slave position. Agreements concluded between free people abound with clauses of this kind.

The boundaries of the economic freedoms of the Babylonian slave were so wide that they even included his right to become a slave owner himself. This, for example, is evidenced by the text of the agreement between the full-fledged Babylonians Iddia, Rimut and Sin-zer-ushabshi, on the one hand, and the slave Id-dahu-Nabu, on the other, concluded in Ur during the reign of Artaxerxes. According to the text of the contract, the sellers received from the buyer 1 mina 18 shekels of silver - the full price of the slave Beltima, and transferred her to the buyer. At the same time, the contract specifically notes the responsibility of the full-fledged Babylonians to the slave in the event that a third party challenges the deal: “As soon as claims to their slave Beltima arise, then Iddiya, the son of Sin-iddin, Rimut, the son of Muranu and Sin-zer-ushabshi, the son Shamash-Etira, must purify their slave Beltima and give them to Id-dahu-Nab” (Figulla 1949: 29). In this context, the word "clear" should be understood as to release from claims, to assume all the costs associated with freeing the property of a slave from encumbrances, and then transfer it to the buyer. As you can see, according to the terms of the contract, the slave became the full owner of the acquired slave and even received guarantees that his acquisition would never be challenged by anyone.

The opportunities granted to the slave to participate as an active (and in some cases even very influential) economic agent in a certain sense brought his economic status closer to the status of persons whose freedom was not limited. The slave's position became even more independent in cases where he was freed from the obligation to live in his master's house. The fact that this actually took place is evidenced by contracts for the rental of rented housing by slaves. It is worth noting, however, that in the cases known to us, the quality of such housing left much to be desired. For example, according to a treaty concluded in 546 BC in Babylon between Shushranni-Marduk, the son of Marduk-nadin-ah, and Bel-tsele-shime, a slave of a full-fledged man named Nabu-ahe-iddin, Shushranni-Marduk provided for the use of Bel-tsele-shime, for a fee of 2 ka of bread per day, a room located on the roof of the barn, as well as an extension near the barn (Strassmaier 1889: 499). It is impossible to say for sure why Bel-tse-shima was not provided with better housing under the contract: whether the reason for this was his low solvency or whether access to the quality housing stock of Babylonia was still differentiated depending on the social status of the tenant. The latter could be supported by the fact that in some contracts of that time housing rented by slaves was called “slave quarters” ( Idem 1892: 163). But, one way or another, the position of a slave, not “physically” tied to the house of his master, in some ways turned out to be even more advantageous in comparison with the position of a full-fledged Babylonian, under the patriarchal authority of the head of the family.

Apparently, the fact that the society of Ancient Mesopotamia provided slaves with significant rights and freedoms in the economic sphere was the result of following a cultural tradition established in Sumer and refracted through the Code of Hammurabi. The legal allowances for slaves were also able to act as an institutional counterbalance to the ease with which a full-fledged person could lose his freedom. But not least of all, this became possible because it was completely consistent with the interests of the slave owners. Probably, in the community of full-fledged people of Mesopotamia, the dominant idea was of the slave not as a thing or a socially humiliated agent, but primarily as a person capable of being a source of constant income. This could explain that in practice, the slave and the owner in most cases were connected not so much by social as by economic dependence, and the slave himself often became the object of investment in human capital. It should not be surprising that under such conditions, slave owners learned to turn a blind eye to class prejudices and were able, with precise usurious calculation, to see their benefit from providing the slave with broad economic autonomy and legal rights.

So, with a more careful examination of the social practices characterizing the position of free and slaves in Sumer, Akkad, Assyria and Babylonia, it is possible to supplement the picture of the social organization of the societies of Ancient Mesopotamia with touches that make it different from the social organization of classical slave societies. Although the existence of slavery here was an indisputable fact, free and slave, who formed the opposition in the social structure, were nevertheless not separated by an insurmountable gulf. People with full rights were under the pressure of numerous state burdens and patriarchal dependence on the head of the family. At the same time, slaves had legal personality and a high degree of freedom in carrying out economic activities, and the opportunity to act as active and influential players in economic life. All this eroded the class contradictions that existed in the societies of Ancient Mesopotamia and opened up the possibilities for people to exercise economic initiative, regardless of their social status. It is no coincidence that for many centuries Mesopotamia demonstrated the continuity of economic culture and became the embodiment of sustainable economic development and social stability.

Literature

The World History economic thought. T. 1. From the origins of economic thought to the first theoretical systems of political life. M.: Mysl, 1987.

Dyakonov, I. M. 1949. Development of land relations in Assyria. LSU.

Story Ancient East. The origins of the most ancient class societies and the first centers of slave-owning civilization. Part I. Mesopotamia. M., 1983.

Kechekyan, S. F. 1944. General History of State and Law. Part I Ancient world. Vol. 1. Ancient East and Ancient Greece. M.

Kozyreva, I. V. 1999. Social Labor in Ancient Mesopotamia. In: Dandamaev, M. A. (ed.), Taxes and duties in the Ancient East: Sat. Art. SPb.: Oriental Studies.

North, D. 1997. Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. M.: Foundation for the Economic Book “Beginnings”.

Severity, D. A. 2014. The process of the emergence of private and state property (based on written sources of Ancient Mesopotamia of the Protoliterate period). Problems of the history of society, state and law(pp. 6–32). Vol. 2. Ekaterinburg: UrGUA.

Tyumenev, A.I. 1956. State economy of Ancient Sumer. M.; L.

Philosophical dictionary / ed. M. M. Rosenthal. M., 1972.

Reader on the history of the Ancient East. Part 1. M.: Higher School, 1980.

Shilyuk, N. F. 1997. History of the Ancient World: Ancient East. 2nd ed. Ekaterinburg: Ural Publishing House. un-ta.

Ebeling, E. 1927. Keilschrifttexte aus Assur juristischen Inhalts. Wissenschaftliche Veroffentlichung der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft. Bd. 50. Leipzig.

Figulla, H.H. 1949. Business Documents of the New-Babylonian period. Ur Excavations Texts. London.

Grice, E.M. 1919. Records from Urand Larsa Dated in the Larsa Dynasty. Vol. VIII. London: New Haven.

Petschow, H. 1956. Neubabylonisches Pfandrecht. Berlin.

Scheil, V. 1915. La liberation judiciaire d'um fils. Revue d'Assyriologie XII.

Strassmaier, J. N.

1889. Inschriften von Nabonidus, Konig von Babylon. Leipzig.

1890. Inschriften von Cyrus, Konig von Babylon. Leipzig.

1892. Inschriften von Darius, Konig von Babylon. Leipzig.

The University of Pennsylvania. The Museum. Publications of the Babylonian Section. Vol. II. Philadelphia, 1912.

Wittfogel, K. A. 1957. Oriental Despotism. A Comparative Study of Total Power. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Yale Oriental Series Babylonian Texts. Vol. VI. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1920.

How not to perish if the two rivers on which your life depends are stormy and unpredictable, and of all earthly riches there is only clay in abundance? The peoples of Ancient Mesopotamia did not perish; moreover, they managed to create one of the most developed civilizations of its time.

Background

Mesopotamia (Mesopotamia) is another name for Mesopotamia (from the ancient Greek Mesopotamia - “mesopotamia”). This is how ancient geographers called the territory located between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. In the 3rd millennium BC. Sumerian city-states, such as Ur, Uruk, Lagash, etc., were formed on this territory. The emergence of an agricultural civilization became possible thanks to the floods of the Tigris and Euphrates, after which fertile silt settled along the banks.

Events

III millennium BC- the emergence of the first city-states in Mesopotamia (5 thousand years ago). The largest cities are Ur and Uruk. Their houses were built from clay.

Around the 3rd millennium BC.- the emergence of cuneiform (more about cuneiform). Cuneiform writing arose in Mesopotamia initially as an ideographic rebus and later as a verbal syllabic writing. They wrote on clay tablets using a pointed stick.

Gods of Sumerian-Akkadian mythology:

- Shamash - god of the Sun,

- Ea - god of Water,

- Sin - god of the moon

- Ishtar is the goddess of love and fertility.

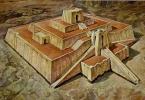

Ziggurat is a temple in the form of a pyramid.

Myths and stories:

- The myth of the flood (about how Utnapishtim built a ship and was able to escape during the global flood).

- The Tale of Gilgamesh.

Participants

To the northeast of Egypt, between two large rivers - the Euphrates and the Tigris - is Mesopotamia, or Mesopotamia (Fig. 1).

Rice. 1. Ancient Mesopotamia

The soils in Southern Mesopotamia are surprisingly fertile. Just like the Nile in Egypt, the rivers gave life and prosperity to this warm country. But the river floods were violent: sometimes streams of water fell on villages and pastures, demolishing dwellings and cattle pens. It was necessary to build embankments along the banks so that the flood would not wash away the crops in the fields. Canals were dug to irrigate fields and gardens.

The state arose here at approximately the same time as in the Nile Valley - more than 5,000 years ago.

Many settlements of farmers, growing, turned into the centers of small city-states, the population of which was no more than 30-40 thousand people. The largest were Ur and Uruk, located in the south of Mesopotamia. Scientists have found ancient burials, the objects found in them indicate the high development of the craft.

In the Southern Mesopotamia there were no mountains or forests; the only building material was clay. The houses were built from clay bricks, dried due to lack of fuel in the sun. To protect buildings from destruction, the walls were made very thick, for example, the city wall was so wide that a cart could drive along it.

In the center of the city rose ziggurat- a high stepped tower, at the top of which there was a temple of the patron god of the city (Fig. 2). In one city it was, for example, the sun god Shamash, in another - the moon god Sin. Everyone revered the water god Ea; people turned to the fertility goddess Ishtar with requests for rich grain harvests and the birth of children. Only priests were allowed to climb to the top of the tower - to the sanctuary. The priests monitored the movements of the heavenly gods - the Sun and the Moon. They compiled a calendar and predicted people's destinies using the stars. The learned priests also studied mathematics. They considered the number 60 sacred. Under the influence of the inhabitants of Ancient Mesopotamia, we divide an hour into 60 minutes, and a circle into 360 degrees.

Rice. 2. Ziggurat at Ur ()

During excavations of ancient cities in Mesopotamia, archaeologists found clay tablets covered with wedge-shaped icons. Badges were pressed onto damp clay with a pointed stick. To impart hardness, the tablets were fired in a kiln. Cuneiform icons are a special script of Mesopotamia - cuneiform. The icons represented words, syllables, and combinations of letters. Scientists have counted several hundred characters used in cuneiform writing (Fig. 3).

Rice. 3. Cuneiform ()

Learning to read and write in Ancient Mesopotamia was no less difficult than in Egypt. Schools, or "Houses of Tablets", appeared in the 3rd millennium BC. e., only children from wealthy families could attend, since education was paid. For many years it was necessary to attend a scribe school in order to master the complex writing system.

Bibliography

- Vigasin A. A., Goder G. I., Sventsitskaya I. S. History of the Ancient World. 5th grade. - M.: Education, 2006.

- Nemirovsky A.I. A book for reading on the history of the Ancient World. - M.: Education, 1991.

Additional precommended links to Internet resources

- Project STOP SYSTEM ().

- Culturologist.ru ().

Homework

- Where is Ancient Mesopotamia located?

- What do the natural conditions of Ancient Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt have in common?

- Describe the cities of Ancient Mesopotamia.

- Why does cuneiform have tens of times more characters than the modern alphabet?

The oldest slave-owning society and states emerged in the southern part of the valley of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers at approximately the same time as in Egypt. Here the second most important center of civilization arises, which had a great influence on the political, economic and cultural history of the entire ancient world.

Decomposition of the primitive communal system in Mesopotamia.

Natural conditions and population of Mesopotamia.

The flat part of the country, located between the Tigris and Euphrates in their lower and middle reaches, is usually called the Greek word Mesopotamia (Interfluve). The natural conditions and historical destinies of the northern and southern parts of Mesopotamia are different. Therefore, its southern part, where the flow of both rivers converged (mainly to the south of the area of the capital of modern Iraq - Baghdad), we distinguish under the name “Mesopotamia”.

This part of the Mesopotamian plain is filled with sediments of rivers that periodically overflow during the spring and summer due to the melting of snow in the upper mountain regions. The most ancient settlements, which were the centers of formation of the first states, were located on both banks along the lower reaches of both rivers, mainly the Euphrates, whose waters are easier to use for agriculture without special water-lifting devices. For use in autumn cultivation of the land, spill waters had to be collected in special reservoirs. The Euphrates and Tigris, in addition to their enormous role as sources of irrigation, are the main transport arteries of the country.

The climate in Mesopotamia is hot and dry. The amount of precipitation is small, and it falls mainly in winter. As a result, agriculture is possible mainly on soils naturally irrigated by river floods or artificially irrigated. On such soils, a wide variety of crops can be grown and high and sustainable yields can be obtained.

The Mesopotamian plain is bordered on the north and east by the marginal mountains of the Armenian and Iranian highlands; in the west it borders on the Syrian steppe and the deserts of Arabia. From the south, the plain is bordered by the Persian Gulf, into which the Tigris and Euphrates flow. Currently, both of these rivers, 110 km before flowing into the sea, merge into a single river stream - the Shatt al-Arab, but in ancient times the sea wedged much deeper to the northwest and both rivers flowed into it separately. The center of the origin of the ancient civilization was located right here, in the southern part of Mesopotamia.

The natural resources that could be used by the ancient population of the plain are small - reeds, clay, and in rivers and swampy lakes - fish. Among tree species, one can note the date palm, which produces nutritious and tasty fruits, but low-quality wood. There was a lack of stone and metal ores necessary for the development of the economy.

The most ancient population of the country, who laid the foundations of civilization in Mesopotamia, were the Sumerians; it can be argued that already in the 4th millennium BC. e. The Sumerians were the main population of Mesopotamia. The Sumerians spoke a language whose relationship with other languages has not yet been established. The physical type of the Sumerians, if you trust the surviving statues and reliefs that usually quite roughly convey the appearance of a person, was characterized by a round face with a large straight nose.

From the 3rd millennium BC. e. Cattle-breeding Semitic tribes begin to penetrate into Mesopotamia from the Syrian steppe. The language of this group of Semitic tribes is called Akkadian or Babylonian-Assyrian, according to the later names that this group of Semites acquired already in Mesopotamia. At first they settled in the northern part of the country, turning to agriculture. Then their language spread to the southern part of Mesopotamia; By the end of the 3rd millennium, the final mixing of the Semitic and Sumerian populations took place.

Various Semitic tribes at this time made up the bulk of the pastoral population of Western Asia; the territory of their settlement covered the Syrian steppe, Palestine and Arabia.

Northern Mesopotamia and the marginal highlands of Iran, bordering the Tigris and Euphrates valleys on the east, were inhabited by numerous tribes who spoke languages whose family ties have not yet been established; some of them may have been close to certain modern Caucasian languages. In the northern part of Mesopotamia and on the tributaries of the Tigris, settlements of the Hurrian tribes are early attested by monuments; further to the east, in the mountains, lived the Lullubei and Gutei (Kutii). The river valleys of Southwestern Iran adjacent to Mesopotamia were occupied by the Elamites.

For the most part, these and tribes close to them in the 4th-3rd millennia BC. e. were settled mountain farmers and semi-sedentary pastoralists who still lived under the conditions of a primitive communal system. It was they who created the Eneolithic “culture of painted ceramics” in Western Asia; their settlements. - Tell Halaf, Tell Brak, Arnachia, Tepe-Gaura, Samarra, and deeper in the highlands of Iran Tepe-Giyan, Tepe-Sialk, Tepe-Gissar, Tureng-Tepe - allow us to judge the nature of the development of the tribes engaged in mining -stream farming during the Neolithic and Eneolithic periods. Most of them at first were still ahead in their development of the tribes that inhabited Mesopotamia, and only from the second half of the 4th millennium the population of Mesopotamia quickly overtook their neighbors.

Only among the Elamites in the lower reaches of the Karuna and Kerkh rivers did class society emerge, only a little later than in Sumer.

Monuments of the 3rd millennium indicate that by sea route along the Persian Gulf. Sumer was connected with other countries. Cuneiform texts mention the island of Dilmun and the countries of Magan and Meluhha, famous for gold and ebony. Only Dilmun is indisputably identified with the present-day Bahrain Islands off the coast of Eastern Arabia, so we cannot definitely say how far the sea connections of Mesopotamia extended. However, epic songs about the travels of Sumerian heroes to the east, “beyond the seven mountains,” and about friendly relations with the local population, as well as seals with images of Indian elephants and signs of Indian writing, which were found in the settlements of Mesopotamia in the 3rd millennium BC. e., make us think that there were connections with the Indus Valley.

Less certain are the data on the earliest connections with Egypt; however, some features of the earliest Chalcolithic culture of Egypt force a number of researchers to assume the existence of such connections, and some historians suggest that in the last third of the 3rd millennium BC. e. There were military clashes between Mesopotamia and Egypt.

Ancient settlements in Mesopotamia.

The example of the history of the peoples of Mesopotamia clearly shows how the influence of the conditions of the geographical environment on the course of historical development is relative. The geographical conditions of Mesopotamia have hardly changed over the last 6-7 thousand years. However, if at present Iraq is a backward, semi-colonial state, then in the Middle Ages, before the devastating Mongol invasion in the 13th century, as well as in antiquity, Mesopotamia was one of the richest and most populated countries in the world. The flourishing of Mesopotamian culture, therefore, cannot be explained only by the country’s favorable natural conditions for agriculture. If we look even further back into the centuries, it turns out that the same country in the 5th and even partly in the 4th millennium BC. e. was a country of swamps and lakes overgrown with reeds, where a rare population huddled along the shores and on islands, pushed into these disastrous places from the foothills and steppes by stronger tribes.

Only with the further development of Neolithic technology and the transition to the Metal Age did the ancient population of Mesopotamia become able to take advantage of those features of the geographical environment that had previously been unfavorable. With the strengthening of human technical equipment, these geographical conditions turned out to be a factor that accelerated the historical development of the tribes who settled here.

Only with the further development of Neolithic technology and the transition to the Metal Age did the ancient population of Mesopotamia become able to take advantage of those features of the geographical environment that had previously been unfavorable. With the strengthening of human technical equipment, these geographical conditions turned out to be a factor that accelerated the historical development of the tribes who settled here.

The oldest settlements discovered in Mesopotamia date back to the beginning of the 4th millennium BC. e., to the period of transition from the Neolithic to the Eneolithic. One of these settlements was excavated under the El Obeid hill. Such hills (tells) were formed on the plain of Mesopotamia on the site of ancient settlements through the gradual accumulation of building remains, clay from mud bricks, etc. The population living here was already sedentary, knew simple agriculture and cattle breeding, but hunting and fishing still played a role big role. The culture was similar to that of the foothills, but poorer. Weaving and pottery were known. Stone tools predominated, but copper products had already begun to appear.

Around the middle of the 4th millennium BC. e. include the lower layers of the Uruk excavations. At this time, the inhabitants of Mesopotamia knew the cultures of barley and emmer, and domestic animals included bulls, sheep, goats, pigs and donkeys. If the dwellings of El Obeid were predominantly reed huts, then during the excavations of Uruk relatively large buildings made of raw brick were found. The first pictographic (drawing) inscriptions on clay tiles (“tablets”), the oldest written monuments of Mesopotamia, date back to this period, the second half of the 4th millennium. The most ancient written monument of Mesopotamia - a small stone tablet - is kept in the Soviet Union in the State Hermitage (Leningrad).

By the end of the 4th and the very beginning of the 3rd millennium BC. include layers of excavations of the Jemdet-Nasr hill, not far from another ancient city of Mesopotamia - Kish, as well as later layers of Uruk. Excavations show that pottery production reached significant development here. Tools made of copper are found in increasing numbers, although tools made of stone and bone are still widely used. The wheel was already known and cargo was transported not only with packs, but on swampy soil on sleds, but also with wheeled vehicles. There were already public buildings and temples built from raw brick, significant in size and artistic design (the first temple buildings appeared at the beginning of the previous period).

By the end of the 4th and the very beginning of the 3rd millennium BC. include layers of excavations of the Jemdet-Nasr hill, not far from another ancient city of Mesopotamia - Kish, as well as later layers of Uruk. Excavations show that pottery production reached significant development here. Tools made of copper are found in increasing numbers, although tools made of stone and bone are still widely used. The wheel was already known and cargo was transported not only with packs, but on swampy soil on sleds, but also with wheeled vehicles. There were already public buildings and temples built from raw brick, significant in size and artistic design (the first temple buildings appeared at the beginning of the previous period).

Development of agriculture.

Those Sumerian tribes that settled in Mesopotamia were able, already in ancient times, to begin in various places in the valley to drain the swampy soil and to use the waters of the Euphrates, and then the Lower Tigris, creating the basis for irrigation agriculture. The alluvial (alluvial) soil of the valley was soft and loose, and the banks were low; therefore, it was possible even with imperfect tools to build canals and dams, reservoirs, dams and dams. Carrying out all this work required a large number of workers, so it was beyond the power of either an individual family, a primitive community, or even a small association of such communities. It became possible at a different, higher level of social development, when the unification of many communities took place.

Work on the creation of an irrigation system was possible only at a certain level of technological development, but they, in turn, inevitably had to contribute to the further development of agricultural technology, as well as the improvement of the tools that were used for digging work. In drainage and irrigation work, tools with metal parts are beginning to be used. In connection with the growth of the irrigation economy, the more intensive use of metal should have led to very important social results.

The growth of labor productivity led to the possibility of producing a surplus product, which created not only the necessary preconditions for the emergence of exploitation, but also led to the emergence in communities that initially conducted collective farming of strong families interested in organizing separate independent farms and striving to seize the best lands. These families eventually form a tribal aristocracy, taking control of tribal affairs into their own hands. Since the tribal aristocracy had better weapons than ordinary members of the community, it began to capture most of the military spoils, which in turn contributed to increased property inequality.

The emergence of slavery.

Already during the period of the decomposition of the primitive communal system, the Sumerian tribes used slave labor (mentions of female slaves, and then slaves, are available in documents from the period of the Jemdet-Nasr culture), but they used it to a very limited extent. The first irrigation canals were dug by free members of the communities, but the development of a large-scale irrigation economy required a significant amount of labor. Free representatives of society continued to work on the creation of the irrigation network, but slave labor was increasingly used for excavation work.

The victorious cities also involved the population of the conquered communities in the work of artificial irrigation. This is evidenced by reflecting the conditions of the beginning)

The victorious cities also involved the population of the conquered communities in the work of artificial irrigation. This is evidenced by reflecting the conditions of the beginning)